Amebiasis is an infection caused by the protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. In contrast, nonpathogenic ameba that infect humans include E. dispar and E. moshkovskii (both morphologically identical to and easily confused with E. histolytica), E. coli, E. hartmanni, and Endolimax nana. Dientamoeba fragilis and E. polecki have been associated with diarrhea and E. gingivalis with periodontal disease. Approximately 50 million illnesses and 100 000 deaths occur annually from amebiasis, making it the third-leading cause of death due to parasitic disease in humans. Long-term consequences of amebiasis in children may include both malnutrition and lower cognitive abilities. Currently there is no vaccine to prevent the childhood morbidity and mortality due to infection with this protozoan parasite. Although amebiasis is present worldwide, it is most common in underdeveloped areas, especially Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. In the United States and other developed countries, cases of amebiasis are most likely to occur in immigrants from and travelers to endemic regions.

Epidemiology

Infection occurs via ingestion of the parasite’s cyst from fecally contaminated food, water, or hands. This is a common occurrence among the poor of developing countries and can afflict populations of the developed world, as the recent epidemic in Tblissi Georgia due to contaminated municipal water demonstrates (Barwick et al., 2002). Carefully conducted serologic studies in Mexico, where amebiasis is endemic, demonstrated antibody to E. histolytica in 8.4% of the population. In the urban slum of Fortaleza, Brazil, 25% of all people tested carried antibody to E. histolytica; the prevalence of antiamebic antibodies in children aged 6–14 years was 40%. A prospective study of preschool children in a slum of Dhaka Bangladesh has demonstrated new E. histolytica infection in 45%, and E. histolytica-associated diarrhea in 9%, of the children annually. Not all individuals are equally susceptible to amebiasis, with certain HLA DR and DQ alleles associated with resistance to infection and disease (Duggal et al., 2004).Pathogenesis

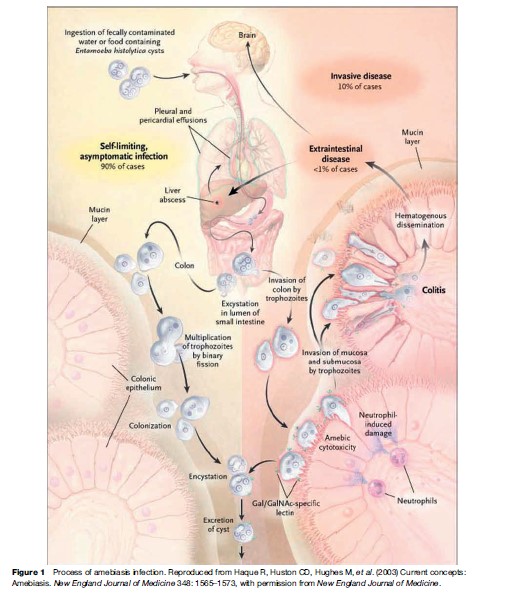

The cysts are transported through the digestive tract to the intestine, where they release their mobile, disease-producing form, the trophozoite. E. histolytica trophozoites can live in the large intestine and form new cysts without causing disease. But they can also invade the lining of the colon, killing host cells and causing amebic colitis, acute dysentery, or chronic diarrhea. The trophozoites can be carried through the blood to other organs, most commonly the liver and occasionally the brain, where they form potentially life-threatening abscesses (see Figure 1). Important virulence factors include the trophozoite cell surface galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Gal/ GalNAc)-specific lectin that mediates adherence to colonic mucins and host cells, cysteine proteinases that likely promote invasion by degrading extracellular matrix and serum components, and amoebapore pore-forming proteins involved in killing of bacteria and host cells. Infection is normally initiated by the ingestion of fecally contaminated water or food containing E. histolytica cysts. The infective cyst form of the parasite survives passage through the stomach and small intestine. Excystation occurs in the bowel lumen, where motile and potentially invasive trophozoites are formed. In most infections, the trophozoites aggregate in the intestinal mucin layer and form new cysts, resulting in a self-limited and asymptomatic infection. In some cases, however, adherence to and lysis of the colonic epithelium, mediated by the galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Gal/GalNAc)-specific lectin, initiates invasion of the colon by trophozoites. Once the intestinal epithelium is invaded, extraintestinal spread to the peritoneum, liver, and other sites may follow. Factors controlling invasion, as opposed to encystation, most likely include parasite ‘quorum sensing’ signaled by the Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin, interactions of amebae with the bacterial flora of the intestine, natural immunity, and innate and acquired immune responses of the host.

Infection is normally initiated by the ingestion of fecally contaminated water or food containing E. histolytica cysts. The infective cyst form of the parasite survives passage through the stomach and small intestine. Excystation occurs in the bowel lumen, where motile and potentially invasive trophozoites are formed. In most infections, the trophozoites aggregate in the intestinal mucin layer and form new cysts, resulting in a self-limited and asymptomatic infection. In some cases, however, adherence to and lysis of the colonic epithelium, mediated by the galactose and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine (Gal/GalNAc)-specific lectin, initiates invasion of the colon by trophozoites. Once the intestinal epithelium is invaded, extraintestinal spread to the peritoneum, liver, and other sites may follow. Factors controlling invasion, as opposed to encystation, most likely include parasite ‘quorum sensing’ signaled by the Gal/GalNAc-specific lectin, interactions of amebae with the bacterial flora of the intestine, natural immunity, and innate and acquired immune responses of the host.

Immunity

Acquired immunity to infection and invasion by E. histolytica is associated with a mucosal IgA antibody response against the carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) of the parasite Gal/GalNAc lectin (Haque et al., 2001, 2006). The average duration of protection afforded by anti-CRD IgA is under 2 years. Cell-mediated immunity in protection from invasive amebiasis, but not infection per se, has also been demonstrated. There is substantial evidence from in vitro animal model and most recently human studies revealed an important role for IFN-g in protection from amebic colitis, acting in part by activating macrophages to kill the parasite. Invasive amebiasis rarely occurs in individuals with HIV/AIDS, even in areas where amebiasis is common, suggesting an important role also for natural resistance and/or innate immune responses in protection from infection.Diagnosis

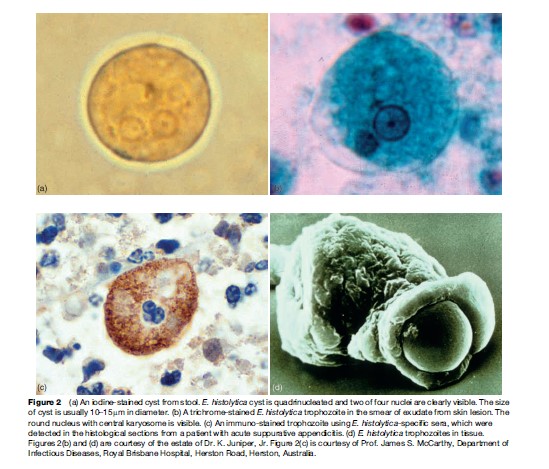

Historically, diagnosis of amebiasis was complicated because several areas of the body can be affected, symptoms may be similar to other conditions such as inflammatory bowel diseases, and diagnostic tests were not highly specific. Before the development of new antigen detection and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, diagnosis of amebiasis was performed by examining a stool sample through a microscope to determine whether E. histolytica cysts were present (Figure 2(a)). However, this method often requires more than one specimen because the number of cysts in the stool is highly variable. In addition, stool microscopy has limited sensitivity and specificity. The body’s own immune system produces macrophages that can look like the ameba. Moreover, three different amebas – E. histolytica, which causes amebiasis, and E. dispar and E. moshkovskii, which do not cause disease – look identical under a microscope (Diamond and Clark, 1993). Amebiasis outside the intestine has been even more difficult to diagnose. Clinical manifestations of extraintestinal disease vary widely, and less than 10% of person with amebic liver abscesses have identifiable E. histolytica in their stools. Noninvasive diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, computer tomographic (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect liver abscesses but cannot distinguish between abscesses caused by ameba and those caused by bacteria, thus hampering proper treatment of the condition. Until recently, the most accurate diagnostic test involved examining a sample of the abscess tissue obtained by needle aspiration (Figure 2(b)), a procedure that is painful, potentially dangerous, and relatively insensitive, identifying amebic trophozoites only 20% of the time.

A stool antigen diagnostic test using polyclonal anti-bodies to adhesin of E. histolytica that allows specific and sensitive diagnosis of E. histolytica infection is manufactured by TechLab, Inc. This FDA-approved test is 80–90% sensitive and nearly 100% specific compared to real-time PCR. The E. histolytica antigen test can be performed rapidly and cheaply, and can detect infection before symptoms appear. Early presymptomatic treatment can prevent the development of invasive amebiasis and minimize the spread of infection. Moreover, follow-up tests can be performed to confirm eradication of intestinal infection. In addition, immunohistochemical staining of ameba is useful in a case difficult to diagnose (Figure 2(c)).

Serologic tests for antiamebic antibodies are also a very useful tool in diagnosis, with sensitivity of 70–80% early in disease and approaching 100% sensitivity upon convalescence. The combined use of serology and stool antigen detection test offers the best diagnostic approach.

Amebiasis outside the intestine has been even more difficult to diagnose. Clinical manifestations of extraintestinal disease vary widely, and less than 10% of person with amebic liver abscesses have identifiable E. histolytica in their stools. Noninvasive diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, computer tomographic (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect liver abscesses but cannot distinguish between abscesses caused by ameba and those caused by bacteria, thus hampering proper treatment of the condition. Until recently, the most accurate diagnostic test involved examining a sample of the abscess tissue obtained by needle aspiration (Figure 2(b)), a procedure that is painful, potentially dangerous, and relatively insensitive, identifying amebic trophozoites only 20% of the time.

A stool antigen diagnostic test using polyclonal anti-bodies to adhesin of E. histolytica that allows specific and sensitive diagnosis of E. histolytica infection is manufactured by TechLab, Inc. This FDA-approved test is 80–90% sensitive and nearly 100% specific compared to real-time PCR. The E. histolytica antigen test can be performed rapidly and cheaply, and can detect infection before symptoms appear. Early presymptomatic treatment can prevent the development of invasive amebiasis and minimize the spread of infection. Moreover, follow-up tests can be performed to confirm eradication of intestinal infection. In addition, immunohistochemical staining of ameba is useful in a case difficult to diagnose (Figure 2(c)).

Serologic tests for antiamebic antibodies are also a very useful tool in diagnosis, with sensitivity of 70–80% early in disease and approaching 100% sensitivity upon convalescence. The combined use of serology and stool antigen detection test offers the best diagnostic approach.