Complementary and alternative medicine are widely available, but mostly outside the formal health system. There are no indigenous types of medical treatment, but many types of alternative medicine including acupuncture, Ayurveda, and ‘new age’ healing methods have been introduced. As these services are largely outside the formal health systems, there are few official statistics on the utilization or the size of the market. However, a 2005 Danish national health survey reported that within the past year 22.5% of the Danish population used alternative treatment and 45.2% of all Danes have used alternative treatment at some point in their lives. Some elements of traditional medicine, such as acupuncture, are now being offered in public health organizations on an experimental basis. The Danish government has established a research center for alternative medicine to collect evidence for such treatments (Videns-Og Forskningscenter for Alternativ Behandling; VIFAB). A similar center exists in Norway (Nationalt Forskningssenter innen Komplementær og Alternativ Medicin (NAFKAM)). Several patient organizations in Denmark (e.g., for cancer, and rheumatic diseases) offer advice and referral to alternative treatment options. Users normally pay direct out-of-pocket payments for services outside the health-care system. There is limited control of the quality and effectiveness of these services because they are outside the system.

Reform Trends

As part of the broader reconsideration of the welfare state, the Danish and Norwegian health-care systems are currently in the midst of substantial structural reform and Sweden is considering such reforms. The region is thus participating in the wave of health-care reforms underway in most Western industrialized countries. This call for reforms has been spurred by several factors. Most important has been the increasing financial burden placed on governments combined with a desire to improve the resource allocation of health services. This development has been paralleled by new public management (NPM) reforms, which emphasize the need to rethink how the public sector organizes and manages itself. In addition, the introduction of new medical technology and therapies, combined with patient and citizen concerns over the access to and quality of health care, have given rise to new demands within health services. Furthermore, health economists have expressed considerable concern about the inefficiency of health services in several Scandinavian countries, given the paucity of evidence of significant improvement in health outcomes despite increasing health spending (e.g., Flood, 2000; Scott, 2001). In the planned market models of Northern Europe, the challenge has been to generate a degree of autonomous management within the system of public hospitals while at the same time securing uniform access and quality levels across the different treatment facilities. Principal elements in proposed reforms include (1) increased competition between health-care providers combined with the use of incentive-based contracts and (2) a greater degree of patient influence both through increased freedom to choose among different providers and guarantees of receiving elective treatments within certain time limits. Efforts to reorganize the incentive structure for providers have been accompanied by a growing body of regulatory measures. The most recent National Health Service reforms in the United Kingdom promised a ‘third way’ between the old command-and-control model and the competitive contracting model: by dismantling the internal market, the goal is to shift the emphasis from competition and choice to an emphasis on cooperation. In the Scandinavian countries, the challenges related to cost increases and the insufficient ability of hospitals to absorb patient inflows have led to the introduction of quasi-market mechanisms, such as waiting list guarantees, patients’ rights to free choice of hospitals, and activity-based funding schemes combined with other NPM-inspired reforms, as well as increased focus on patient pathways, integrated care, and prevention and health promotion coordinated among different public authorities.Performance

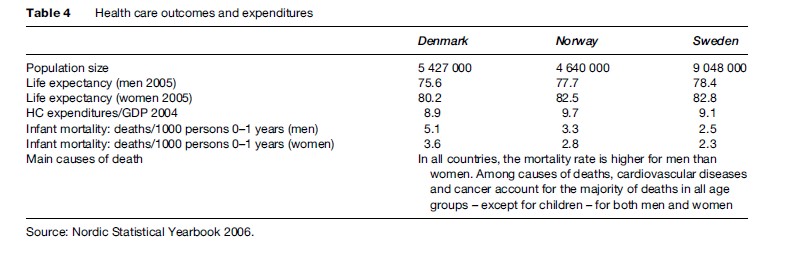

The performance of the Scandinavian health-care model has been the subject of debate (see Table 4). Proponents of the Scandinavian welfare model feel strongly that it has been a great success, referring to it as the ‘most advanced’ and ‘most developed’ stage of the welfare state. Certainly, it is the most comprehensive welfare state in terms of government effort put into welfare provision (Kuhnle, 2000). At the core of the model lie the principles of universalism and broad public participation in various areas of economic and social life, which are intended to promote an equality of the highest of standards rather than an equality of minimal needs. Criticisms have included long waiting lists, excessive bureaucracy, a lack of responsiveness to more fundamental issues about public sector monopsony and/or monopoly in service provision, and a resulting low-quality level. Although the welfare state is highly valued in the Scandinavian countries, observers outside the region sometimes find the Scandinavian approach to be too static in character, with a strong governmental role that deprives the citizenry of important individual freedoms. Other observers praise the egalitarian nature and a degree of security found in the Scandinavian welfare states, but argue that it creates a monotonous uniformity in which the spirit of creativeness and personal initiative has been lost (Erikson et al., 1987). With the era of strong social democratic dominance of Scandinavian politics seemingly coming to an end and being replaced by the increasing success of the political right, there is a growing awareness inside the Scandinavian countries that there may be other possible welfare providers than the state. This major ideological shift acknowledges that state monopoly of welfare provision may not be optimal, that maximum state-organized welfare is not necessarily an expression of the most progressive welfare policy, that voluntary organizations offer other qualities in welfare provision, that market competition can stimulate both better and more efficient health service delivery, and that the tradition of government-run welfare can undermine individual initiative and threaten economic prosperity (Kuhnle, 2000). The challenge for the Scandinavian health systems will be to integrate such insights while at the same time maintaining the benefits achieved in the public welfare system.

Bibliography:

With the era of strong social democratic dominance of Scandinavian politics seemingly coming to an end and being replaced by the increasing success of the political right, there is a growing awareness inside the Scandinavian countries that there may be other possible welfare providers than the state. This major ideological shift acknowledges that state monopoly of welfare provision may not be optimal, that maximum state-organized welfare is not necessarily an expression of the most progressive welfare policy, that voluntary organizations offer other qualities in welfare provision, that market competition can stimulate both better and more efficient health service delivery, and that the tradition of government-run welfare can undermine individual initiative and threaten economic prosperity (Kuhnle, 2000). The challenge for the Scandinavian health systems will be to integrate such insights while at the same time maintaining the benefits achieved in the public welfare system.

Bibliography:

- Eriksson R, Hansen EJ, Ringen S and Uusitalo H (eds.) (1987) The Scandinavian Model. Welfare States and Welfare Research. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Ervik R and Kuhnle S (1996) The Nordic welfare model and the European Union. In: Greve B (ed.) The Scandinavian Model in a Period of Change, pp. 87–110. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press.

- Esping-Andersen G (1999) Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Flood CM (2000) International Health Care Reform: A Legal, Economic, and Political Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Johnsen JR (2006) Health systems in transition: Norway. WHO Regional Office for Europe on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO.

- Kautto M, Fritzell J, Hvinden B, Kvist J and Uusitalo H (eds.) (2001) Nordic Welfare States in the European Context. London: Routledge.

- Kristiansen IS and Pedersen KM (2000) Helsevesenet i de nordiske land – er likhetene større enn ulikhetene? Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association 120: 2023–2029.

- Kuhnle S (2000) The Nordic welfare state in a European context: Dealing with new economic and ideological challenges in the 1990s. European Review 8: 379–398