Leishmania are dimorphic parasites that present as two principal morphological stages: the intracellular amastigote, in the cells of the mammalian host mononuclear phagocyte system, and the flagellated promastigote, in the intestinal tract of the insect vector.

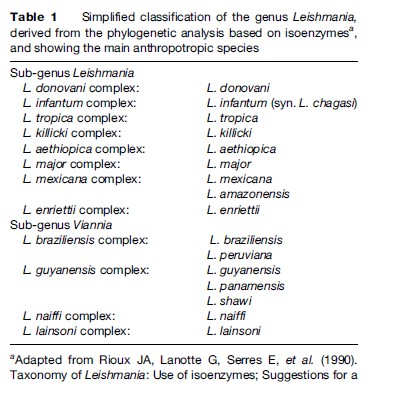

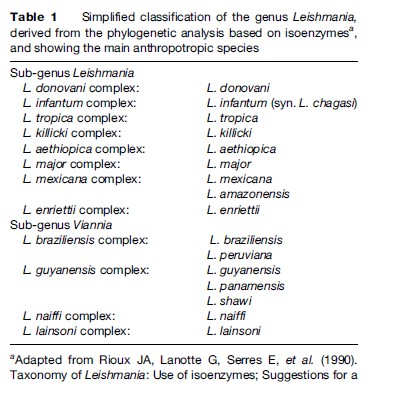

Since the first Leishmania species was described (Laveran and Mesnil, 1903), the number of species has increased steadily, and currently stands around 30. As the different species are morphologically indistinguishable, other characteristics have been used for their taxonomy. Although DNA-based methods are increasingly being used, isoenzyme electrophoresis remains the gold standard technique for identification and is the basis for the current classification (Table 1).

Vector

Sandflies are psychodid Diptera of the subfamily Phlebotominae. Their life cycle includes two different biological stages: the free-flying adult and the developmental stages, which include egg, four larval instars, and pupa, and occur in damp soil rich in organic material.

The adults are small flying insects about 2–4 mm in length, with a yellowish hairy body. During day, they rest in dark, sheltered places. They are active at dusk and during the night. Both sexes feed on plant juices, but females also need a blood meal before they are able to lay eggs. It is during this blood meal that Leishmania parasites are transmitted between the mammalian hosts.

Among the 800 known species of sand flies, about 70, belonging to the genera Phlebotomus in the Old World and Lutzomyia in the New World, are proven or suspected vectors of Leishmania, and a certain level of specificity exists between Leishmania and sand fly species.

Reservoir

Various species of seven different orders of mammals are the reservoir hosts responsible for long-term maintenance of Leishmania in nature. Depending on the focus, the reservoir host can be either a wild or a domestic mammal, or even in particular cases human beings. In visceral leishmaniasis, these different types of reservoir host represent different steps on the hypothetical path toward ‘anthropization’ of a ‘wild’ zoonosis (Garnham, 1965). Rodents, hyraxes, marsupials, and edentates are common reservoirs of wild zoonotic CL. Dogs are currently considered as true reservoirs of L. infantum and L. peruviana, two species that have peri-domestic or even domestic transmission. Humans are the commonly recognized reservoir of L. donovani VL and L. tropica CL.

Life Cycle And Transmission

In nature, Leishmania parasites are alternately hosted by the insect (flagellated promastigote) and by mammals (intracellular amastigote stage). Leishmaniasis is normally transmitted to humans by the inoculation of metacyclic promastigotes through the sand fly bite. Other routes remain exceptional. Exchange of syringes is thought to explain the high prevalence of L. infantum/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) co-infection in intravenous drug users in southern Europe (Alvar and Jimenez, 1994).

Geographical Distribution

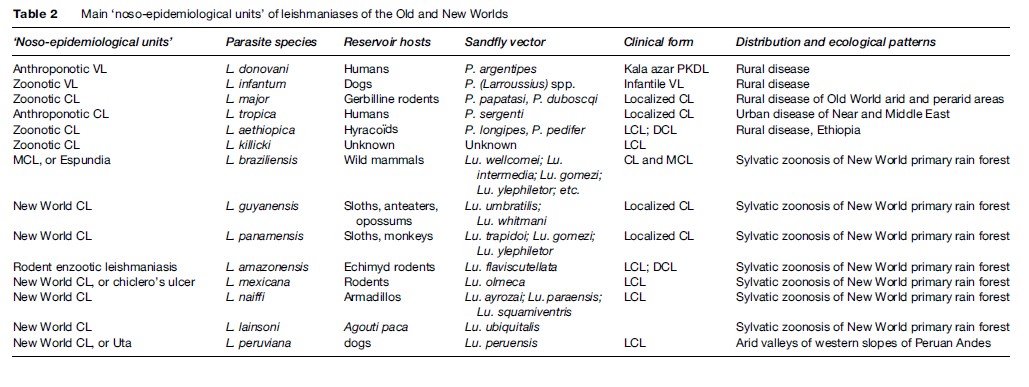

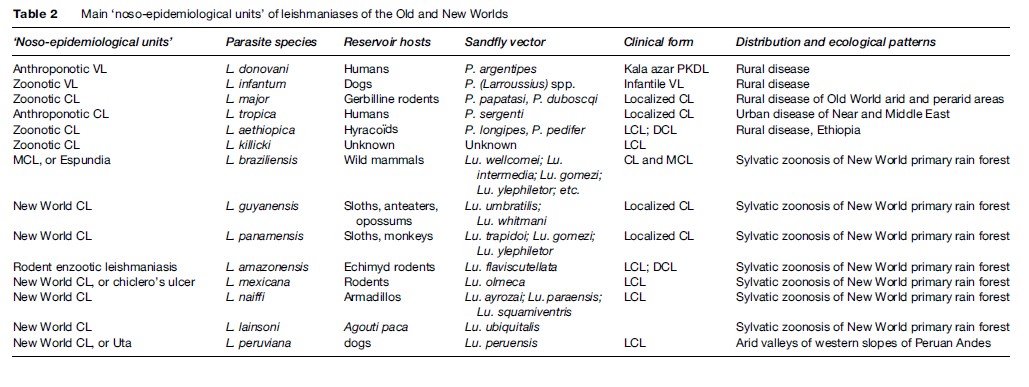

Leishmaniasis occurs in more than 88 countries, ranging over the intertropical zones of America and Africa, and extending into temperate regions of South America, southern Europe, and Asia. The limits of the disease are latitudes 45 north and 32 south. The geographical distribution is governed by those of the mammal or sand fly host species, their ecology, and their own distribution area. The leishmaniases are diseases with natural focality. They include several ‘noso-epidemiological units,’ which can be defined as the conjunction of a particular Leishmania species circulating in specific natural hosts, evolving in a natural focus with specific ecological patterns, and having a particular clinical expression (see Table 2).

Visceral Leishmaniasis

The two viscerotropic species of Leishmania have distinct life cycles and geographic distribution. The anthroponotic species L. donovani is restricted to India and East Africa. The disease is known as ‘kala-azar’ and can be complicated by a chronic CL form called ‘post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis.’ The zoonotic species L. infantum extends from China to Brazil, and is responsible for infantile VL. The main historical foci of endemic VL are located in China, India, Central Asia, East Africa, the Mediterranean basin, and Brazil.

Old World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The large majority of Old World CL cases are due to the species L. major or L. tropica and occur mainly in countries of the Near and Middle East: Afghanistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. L. major is responsible for zoonotic CL, of which reservoir hosts are gerbilline rodents, and vectors are sand flies of the subgenus Phlebotomus, principally Phlebotomus papatasi and P. duboscqi. This species has a wide distribution, including west, north, and east Africa, the Near and Middle East, and Central Asia.

L. tropica is an anthroponotic species with humansacting as reservoir hosts and the vector being P. (Paraphlebotomus) sergenti. It occurs in various cities of the Near and Middle East, but extends also to Morocco, where the dog is suspected to be a reservoir host in some foci.

Other species have restricted distributions: L. aethiopica in Ethiopia and Kenya, and L. killicki in Tunisia.

New World Tegumentary Leishmaniasis

In the New World, L. braziliensis is the species responsible for MCL. It has a wide distribution, extending from southern Mexico to northern Argentina. L. amazonensis has a wide South American distribution, but human cases of this rodent enzootic species are unusual. Other species have more restricted distributions: L. guyanensis (north of the Amazon basin), L. panamensis (Colombia and Central America), L. mexicana (Mexico and Central America), and L. peruviana, which is restricted to Andean valleys of Peru. With the exception of this last species, all American dermotropic species are responsible for sylvatic zoonoses occurring within the rain forest.

Disease Burden

An estimated 350 million people in more than 88 countries on four continents are ‘at risk’ of leishmaniasis. The annual incidence of new cases, including all clinical forms, is estimated between 1.5 and 2 million (Desjeux, 1999). Differences in morbidity, or even in mortality, depend on the form of the disease. The clinical expression of leishmaniasis depends not only on the genetically determined tropism of the different Leishmania species (viscero-, dermo-, or mucotropisms) but also on the immunological status of the infected patient.

Morbidity And Mortality Of VL

VL is the most severe form of leishmaniasis, with a high untreated fatality rate (around 90% in fully developed disease, though a high proportion of people may become immune without becoming sick). It is found in 47 countries, and the mean annual incidence is estimated around 500 000 new cases. At the present time, 90% of the VL cases in the world are in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil. The Bihar state of India experienced a dramatic epidemic with more than 300 000 cases reported between 1977 and 1990, with a mortality rate over 2%. In western Upper Nile Province in southern Sudan, an outbreak was responsible for 100 000 deaths from 1989 to 1994, in a population of less than 1 million.

In endemic VL countries, asymptomatic Leishmania infections are numerous, which do not lead to clinical outcome except in immunosuppressed individuals.

Morbidity Of CL

Whatever the species responsible, localized CL is normally a self-healing disease with spontaneous cure occurring within between 6 months and a few years, depending on the Leishmania species. Cured lesions are accompanied by permanent scars. Multiple lesions, or those located on the face, may be disabling. Some species, such as L. tropica, are responsible for long-lasting recidivans leishmaniasis.

In patients with a specifically defective cell-mediated immune response, some species (Table 2) are responsible for diffuse cutareous leishmaniasis (DCL), a severe form of the disease characterized by nodular disseminated skin lesions, subject to relapses and resistant to treatment.

Morbidity Of MCL

After a primary cutaneous self-healing lesion, the species L. braziliensis can cause later secondary involvement of facial mucosae. This form led to disfiguring and mutilating facial lesions, greatly affecting life conditions.

Risk Factors

Environmental Risk Factors

Human intrusion into a leishmaniasis natural focus represents the major risk factor of infection by exposure to sand fly vectors. For example, in the case of sylvatic zoonotic New World CL, leisure or work activities in tropical rain forests expose individuals or groups to infection (see Table 2). Population movements, such as rural to suburban migration, returnees, and refugees due to civil unrest, are factors for the spread of leishmaniasis or for dramatic epidemic outbreaks by exposing thousands of nonimmune individuals to infection (Desjeux, 2001). In several endemic countries, a dramatic increase in the number of leishmaniasis cases has occurred in the last decade: Brazil, several countries of the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa (Desjeux, 200