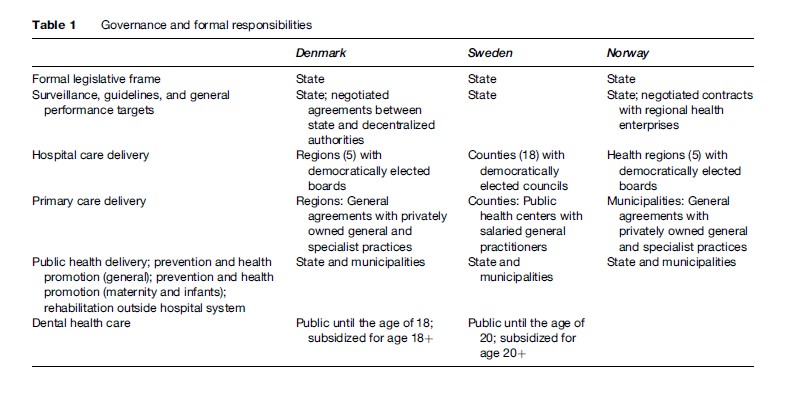

Governance takes place at the municipality and regional level, but within nationally set rules and guidelines (see Table 1). There are institutionalized forums for negotiation between decentralized authorities and the state. In Denmark this negotiation takes place annually as part of the budget negotiations for the municipalities and regions. The Associations of Municipalities and Regions enter into agreements on behalf of their members, although they do not have legally binding means of sanctioning the agreements. The state may sanction agreements by withholding block grants or by legislative intervention. However, in most cases the decentralized institutions follow the agreements. The agreements specify the economic frame, the average taxation rate at the decentralized level, and details of organizational initiatives and programs.

Similar although less institutionalized mechanisms for coordination of policies between the central and the decentralized authorities exist in Sweden, although the Swedish counties have a relatively large degree of autonomy, which has resulted in different organizational and managerial models across the country. Several Swedish counties have experimented with purchaser-provider splits in different forms.

The Norwegian health regions have a semi-independent status, but the national government can influence them in several important ways. First, the state appoints the members of the regional health management boards. Second, the state can influence the articles of association, steering documents (contracts), and decisions adopted by the regional health management boards. The health ministry has attempted to separate a formal steering dialogue from the more informal arenas of discussion ( Johnsen, 2006). Third, the state finances most hospital activities, and there is a formal assessment and monitoring system – with reports on finances and activities submitted to the ministry. On the one hand, hospitals are part of a command-and-control system hierarchy because the state owns them and can mandate policy. On the other hand, the hospitals have gained more autonomy since healthcare professionals replaced county politicians, and the hospital structure today more closely resembles a corporation than a public administration body. Norwegian regions have the formal autonomy to differ in terms of management models, but so far have chosen very similar models ( Johnsen, 2006).

Similar although less institutionalized mechanisms for coordination of policies between the central and the decentralized authorities exist in Sweden, although the Swedish counties have a relatively large degree of autonomy, which has resulted in different organizational and managerial models across the country. Several Swedish counties have experimented with purchaser-provider splits in different forms.

The Norwegian health regions have a semi-independent status, but the national government can influence them in several important ways. First, the state appoints the members of the regional health management boards. Second, the state can influence the articles of association, steering documents (contracts), and decisions adopted by the regional health management boards. The health ministry has attempted to separate a formal steering dialogue from the more informal arenas of discussion ( Johnsen, 2006). Third, the state finances most hospital activities, and there is a formal assessment and monitoring system – with reports on finances and activities submitted to the ministry. On the one hand, hospitals are part of a command-and-control system hierarchy because the state owns them and can mandate policy. On the other hand, the hospitals have gained more autonomy since healthcare professionals replaced county politicians, and the hospital structure today more closely resembles a corporation than a public administration body. Norwegian regions have the formal autonomy to differ in terms of management models, but so far have chosen very similar models ( Johnsen, 2006).

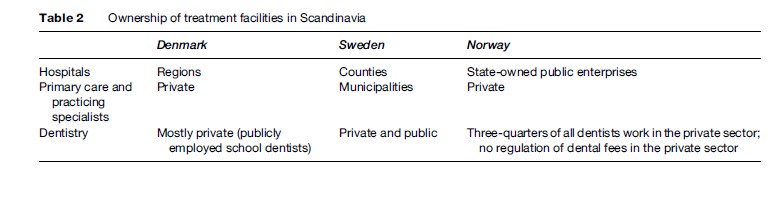

Ownership

Ownership of hospitals is predominantly public (see Table 2). Until recently most hospitals were owned by the county/region in all three Scandinavian countries. However, the Norwegian reform in 2002 moved ownership to the state level, and the Danish reform of 2007 replaced the counties with five regions that took over the ownership of hospitals. A few specialty hospitals in the three countries are owned by patient organizations and operated on a nonprofit basis. All three countries have considered organizational forms in the gray zone between public and private management. Sweden has gone furthest in privatizing a major hospital in Stockholm, whereas Denmark and Norway have experimented with various types of public enterprises that have larger degrees of financial and managerial freedom than regular public hospitals. The Norwegian health reform of 2002 formally placed ownership at the state level, but established an enterprise model with five regional authorities and a higher degree of autonomy for hospital managers.

The picture is even more diverse when looking at general and specialist physician practices. Denmark and Norway have a long tradition of private practice, whereas Sweden relies on public health centers staffed by municipally employed health professionals. The status of private practitioners in Denmark and Norway should be seen in the context of the health-care system in those countries. Entry into practice is strongly regulated, and both general practitioners (GPs) and specialists are included in the public planning of services. GPs generally play an important role as gatekeepers to the Scandinavian health systems. Private practitioners also predominantly receive their income through public funding based on centrally negotiated fees. Thus, in terms of planning, fees, and incomes, private practitioners are very integrated into the public system.

All three countries have considered organizational forms in the gray zone between public and private management. Sweden has gone furthest in privatizing a major hospital in Stockholm, whereas Denmark and Norway have experimented with various types of public enterprises that have larger degrees of financial and managerial freedom than regular public hospitals. The Norwegian health reform of 2002 formally placed ownership at the state level, but established an enterprise model with five regional authorities and a higher degree of autonomy for hospital managers.

The picture is even more diverse when looking at general and specialist physician practices. Denmark and Norway have a long tradition of private practice, whereas Sweden relies on public health centers staffed by municipally employed health professionals. The status of private practitioners in Denmark and Norway should be seen in the context of the health-care system in those countries. Entry into practice is strongly regulated, and both general practitioners (GPs) and specialists are included in the public planning of services. GPs generally play an important role as gatekeepers to the Scandinavian health systems. Private practitioners also predominantly receive their income through public funding based on centrally negotiated fees. Thus, in terms of planning, fees, and incomes, private practitioners are very integrated into the public system.

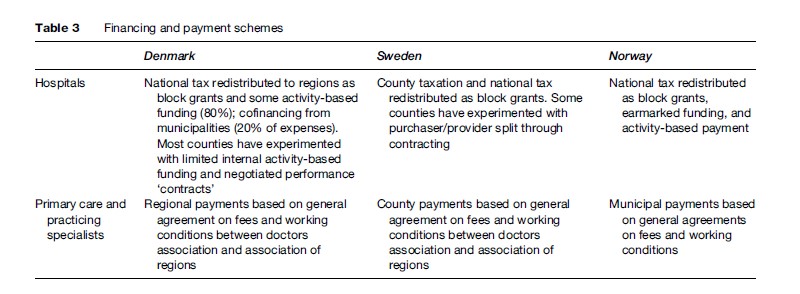

Financing And Payment Schemes

All three countries predominantly rely on public financing of health services (see Table 3). Because of adherence to the overall principles of equity and universal coverage, there is limited user payment for selected services. National taxation is the primary source of funding in Denmark and Norway, whereas Sweden is more decentralized in terms of financing. National funding is redistributed to decentralized authorities in the form of block grants calculated on ‘objective criteria,’ such as population size and composition and activity-based funding. Norway has been most willing to experiment with activity-based financing, whereas some Swedish counties have experimented with purchaser-provider splits starting in the 1990s.