Because estrogens are prothrombotic, there are theoretical reasons for predicting that women taking exogenous estrogens in the form either of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) would have an increased risk of occlusive cardiovascular events. This prediction was certainly fulfilled for first-generation OCPs, which had relatively high levels of estrogen. It is likely that modern, lower-dose contraceptive pills carry a smaller relative risk, and the absolute risk of an acute coronary event or stroke in a woman taking OCPs has always been small, because the background risk of such events in women of reproductive age is very small indeed. HRT stands to mitigate many of the metabolic changes consequent on menopause that are likely to increase cardiovascular risk. Formal proof of the hypothesis that HRT would also reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events is still awaited, because one large trial testing this prediction was suspended prematurely once it became clear that women taking HRT also had a significant increase in the risk of thromboembolic cardiovascular events and of developing breast cancer (Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators, 2002). Subsequent reports have tended to confirm that HRT increases risk of CVD (Vickers et al., 2007).

Socioeconomic Position

While the incidence of IHD originally showed a positive relationship with socioeconomic position, that association has now been reversed so that the least well-off have the highest rates of CVD in Western developed countries, although this transition is occurring later in developing countries. Important variations in the social distributions of many of the other behavioral risk factors for CVD almost certainly contribute to this picture and, given the available evidence, strategies to modify those factors are likely to reduce social gradients in cardiovascular health much faster than interventions to reduce disparities in economic circumstances.Other Risk Factors

There is a considerable literature on hyperuricemia as a marker of cardiovascular risk, and it is well recognized that hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of CVD. There is also reasonable evidence for other putative risk factors (Marmot and Elliott, 2005).Multiple Risk Factors

From a population perspective, there is ample evidence that the combined effects of multiple risk factors contribute to differences in rates of CVD between countries and changes in risk factor levels are related to changes in rates of CVD events (Tunstall-Pedoe, 2003). While the statistical relationships between risk factors and the experience of CVD are complex, patients, clinicians and public health authorities can find these matters easier to discuss in terms of summary numbers for relative risk. As a great oversimplification, each of smoking, hypertension, and inadequate physical activity doubles an individual’s risk of a major cardiovascular event, and hypercholesterolemia and diabetes increase risk by up to three times, each of these comparisons being with individuals who do not have the relevant risk factor. Where more than one risk factor is present, the effects multiply, such that an inactive smoker with high blood pressure has approximately eight times the risk of experiencing a major cardiovascular event compared with a physically active, normotensive nonsmoker. While this approach facilitates discussion between patients and their clinicians, it ignores the graded relationships between each of the major modifiable factors and cardiovascular risk and also omits the individual’s fixed factors from the consideration. Thus, there has been a concerted move in recent years to encourage a more all-encompassing assessment of individual patients and population groups, the results of which are usually expressed in terms of absolute cardiovascular risk. This is the probability that a given individual will experience a major cardiovascular event in the next decade, given his or her sex and age and existing levels of each of at least smoking, blood pressure, and blood total cholesterol (Smith et al., 2004). Relative risk, comparing smokers with non-smokers, for example, can be somewhat misleading; the numerical multiplier might be large, but if it is applied to a low background risk such as the incidence of CVD in women in the reproductive age group, the resulting absolute risk is still modest. By contrast, as well as being more comprehensive, the approach based on absolute risk fosters concentration of intervention efforts on those likely to gain most (Smith et al., 2004). The presence of multiple risk factors also comes into play in the concept of the metabolic syndrome. This refers to a clustering of abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, abnormalities of lipid profiles, and insulin resistance, but this is an evolving area, with multiple definitions of the syndrome available. Apart from identifying a possibly sizeable subgroup of the population at particularly high risk of CVD, it is not yet clear what advantages the label of metabolic syndrome offers for clinical management of cardiovascular risk over and above attention to each of the principal elements of the cluster of risk factors.Practical Steps For Prevention Of Cardiovascular Disease

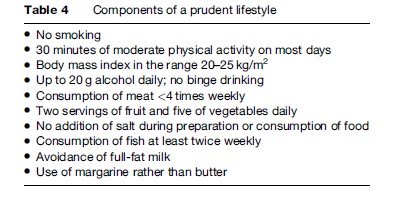

It has now been over 25 years since Geoffrey Rose first identified the inherent limitations in the high-risk strategy, used alone, for improving the health of the population and suggested that mass strategies aimed at whole communities had potentially greater impact (Rose, 1981). The goal for public health is therefore to achieve population-level reductions in the major modifiable risk factors by shifting the risk factor distribution to the left through primary prevention (the population approach) as well as secondary prevention in individuals at elevated risk. Much can be achieved through population-level interventions, such as tobacco control using education, legislation, and taxation. Nevertheless, the development and implementation of effective mass strategies for the prevention of CVD (and noncommunicable diseases more generally), and specifically strategies that address multiple risk factors, remains a challenging problem. Table 4 lists ten behaviors for which there is a varying degree of epidemiological evidence of an association with lower rates of morbidity and mortality, principally from CVD and common cancers. For some of these, such as not being a smoker, there is ample evidence that the imprudent counterpart has a causal association with ill-health. For others, such as type of milk consumed, the significance may lie in indicating acceptance or nonacceptance of a broader message about reducing consumption of saturated fat. Importantly, no involvement of a health professional is required to assess these behaviors and many are potentially amenable to mass interventions. These behaviors are within the grasp of most individuals with adequate resources and supportive environments. In addition, once adopted, many can become permanent, even automatic parts of an individual’s lifestyle. They become habits that are truly healthy and for which only very modest ongoing mental effort is required for their maintenance. For example, it is not a matter of permanently being on a diet, but one of having adopted a pattern of eating and drinking that is enjoyable but also consistent with best available medical knowledge and not conducive to gaining weight. Several of the behaviors in Table 4 are determinants of medically defined risk factors such as hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. A focus on the prudent lifestyle therefore addresses primary prevention and obviates the need for screening that is inherent in the high-risk approach (Rose, 1981). This distinction is in keeping with Rose’s description of mass strategies as being radical, in the sense of preventing the development of risk, while high-risk strategies are palliative, because they address risk that has become established (Rose, 1981).

While the components of a prudent lifestyle may be largely amenable to individual choice, many are also strongly affected by cultural norms (such as the Mediterranean diet), legislative controls (for example, on smoking), and environmental factors (for example, promoting opportunities for physical activity).

Several of the behaviors in Table 4 are determinants of medically defined risk factors such as hypertension or hypercholesterolemia. A focus on the prudent lifestyle therefore addresses primary prevention and obviates the need for screening that is inherent in the high-risk approach (Rose, 1981). This distinction is in keeping with Rose’s description of mass strategies as being radical, in the sense of preventing the development of risk, while high-risk strategies are palliative, because they address risk that has become established (Rose, 1981).

While the components of a prudent lifestyle may be largely amenable to individual choice, many are also strongly affected by cultural norms (such as the Mediterranean diet), legislative controls (for example, on smoking), and environmental factors (for example, promoting opportunities for physical activity).

Prevalence Of A Prudent Lifestyle

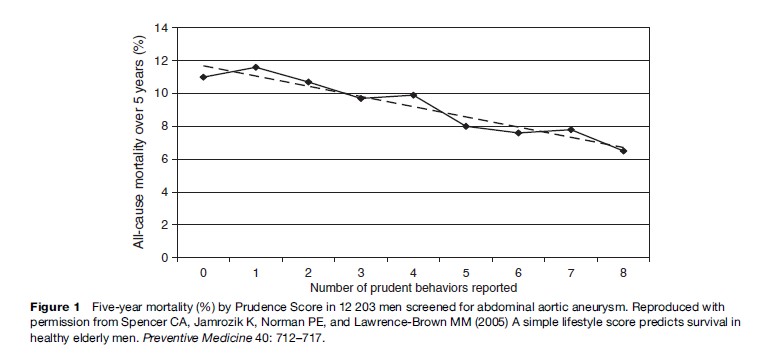

As part of the baseline assessment undertaken in the course of a population-based trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), Spencer et al. ascertained the adherence of 12 203 men aged 65–83 years to eight of the behaviors listed in Table 4 (Spencer et al., 2005). The resulting lifestyle scores, calculated as the simple sum of eight dichotomous answers, showed a bell-shaped distribution, indicating that the majority of these individuals already exhibited some health consciousness. By the same token, however, the majority also has scope to adopt additional elements of the prudent lifestyle. Combining these two interpretations suggests that most individuals have a base of health-related self-efficacy upon which they could draw when attempting to make changes to their lifestyle. Prospective follow-up over 5 years of these men showed that, among those with no history of major cardiovascular events or angina, cumulative all-cause mortality decreased in an almost linear fashion from 12% among those with a lifestyle score of 0 to 6% among those with the maximum prudence score of 8 (see Figure 1) (Spencer et al., 2005). When the data were divided at the median lifestyle score of 4, the lower half had a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.3 (95% CI, 1.1–1.5) relative to the upper half. The findings in men with clinically evident vascular disease were similar. Thus the Prudence Score is not only simple to calculate, it also has considerable prognostic significance.

Conclusion

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death of humans. Our knowledge of factors contributing to the risk of CVD is both extensive and very detailed. We now understand that, for many of the important causal factors, risk rises progressively with the degree of exposure rather than exhibiting some sort of threshold. Thus, while easy to apply, clinical dichotomies between ‘normal’ and ‘at risk’ are simplistic and misleading. Further, there is abundant evidence from both observational studies and randomized trials that reducing levels of major modifiable factors is quickly followed by decreases in the incidence of major cardiovascular events. It follows that advice regarding prudent lifestyle and behavior in relation to risk of CVD is almost universally relevant and should not be delivered only to a selected subgroup of the population bearing a particularly adverse profile of risk factors. The pressing challenge is to broaden the understanding and application of this principle among both health professionals and policy makers; it is to apply better what we already know to control CVD in population, not to search for new risk factors.We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done; and there is no health in us. (Church of England, 1992)Bibliography:

- Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration (Writing Committee: Patel A, Barzi F, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Lawes C, Ueshima H, Whitlock G, Woodward M) (2004) Serum triglycerides as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. Circulation 110: 2678–2686.