Introduction

There are many ways that health-care providers can be paid. In India, government physicians are paid a salary and in Canada physicians are generally paid according to a government-regulated fee schedule. In the Netherlands, however, office-based physicians receive capitated payments for much of their revenue. Similar variations are seen in payments to hospitals, which may be paid using fixed budgets, detailed fee schedules, or episode-based systems. This research paper establishes a conceptual framework for thinking about methods of provider payment by focusing on payments to primary care doctors and to acute care hospitals. Both how payments are made and the market setting can affect the cost, quantity, and quality of care provided, so how payments affect incentives is also discussed. The section titled ‘Performance-based payment systems’ discusses recent payment systems that reward selected performance measures. The focus of this research paper is on payments made to providers by social health insurance, private health insurance, other health plans, governments, and employers. These payments are not made by consumers, thus economists call them supply side payments. Demand side payments (often called cost sharing) are those made by consumers directly to providers. Clearly provider compensation and incentives are impacted by both supply and demand side payments, but this research paper focuses on supply side payments only. There are four broad dimensions of provider payment. The first dimension is the type of information used to calculate payments. The second is the breadth of provider payment: Are doctors and hospitals paid narrowly for their own services, or are they paid broadly for bundles of related services, such as laboratory tests and other provider services? The third dimension of payment is the coarseness of the payment classification system used: Are there relatively few payment categories or are there many? The fourth dimension is the generosity of the payments: Are payments low or high? Each of these dimensions is discussed in the following sections, including how common payment systems use each element and the incentive properties of each method of payment.Information Used For Provider Payment

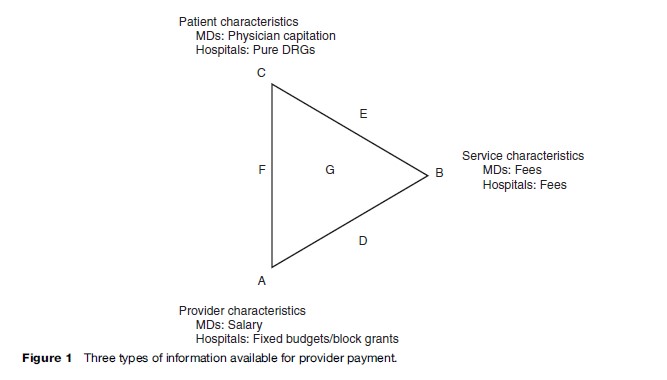

Every provider payment system can be characterized by the information used to calculate provider payments. This information can be based on provider characteristics, patient characteristics, or the characteristics of the services provided. Each type of information can be conceptualized as forming a triangle, as displayed in Figure 1. Provider payments can either use information of one type as represented by the vertexes of the triangle, or payments can be based on hybrids of two or three types of information, as represented by the sides and interior of the triangle. At one extreme, point A in Figure 1, payments only depend on the provider’s own characteristics. For example, doctors can be paid a salary regardless of how many or which patients they see and regardless of what services they provide. These salaries may vary by provider characteristics, such as specialty, training, or experience. In many countries, including India and South Africa, public sector doctors are paid a salary. Even in the United States, doctors working for the federal Veterans’ Administration and doctors in certain staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are paid a salary. Similarly, in many countries, hospitals receive ‘block grants’; block grants are budgets based on hospital size or type without explicit regard to the number or type of patients seen or the services provided. Many public hospitals, including those in Spain and France, receive fixed annual budgets. Such hospital payment systems invariably adjust for variables such as the numbers of beds or population served, but these are still more correctly thought of as features of the provider and their market rather than patient or service characteristics. For a useful discussion of France’s fixed budget system, see Sauvignet (2005).

Another payment system is represented by point B in Figure 1, in which payments are based solely on the health services provided. Fee-based and cost-based payment systems each pay providers according to the quantity of services given. Payments do not depend on who provides the services or who receives them. Under a fee system providers are paid for each service provided and hence are often called fee-for-service (FFS) payment. Fee payment systems can either allow the provider or the payer to set fee levels. Fee schedules set by the payer are the most common form of reimbursement for doctors; they are used in Canada, Germany, Norway, and the United States. Under a cost-based system, providers may be reimbursed at the end of the year for the cost of inputs (lab material, supplies, and staff salaries) regardless of how these inputs are used. In both cases, if providers use more resources to treat patients, revenues increase.

A third possibility (point C in Figure 1) is that provider payments are based exclusively on patient characteristics. A pure capitation system is a payment system based on patient characteristics. Under capitation, physicians receive a fixed amount of money for each patient they manage. Thus, a physician’s gross income depends on the total number of people he or she cares for; the physician’s income does not depend on the type of provider administering the service, the type of service being provided, or the quantity of services provided. Physician capitation payments were made during the 1990s to general practitioners in the United Kingdom and are used today in the Netherlands (Exter et al., 2004). Similarly, hospitals can be paid according to a pure Diagnostic Related Grouping (DRG) payment system. Under a pure DRG payment system, a hospital receives a fixed amount determined solely by the patient’s diagnostic group. Again, the hospital’s revenue only depends on the patients’ characteristics, not on the provider or service characteristics.

Payment systems are not limited to the three cases corresponding to points A, B, and C; providers can be compensated according to hybrids of different dimensions. Some systems are based on a hybrid of provider and service characteristics, corresponding to point D in Figure 1. The office physician payment system in Germany currently has features that make it appear this way. Although doctors receive FFS reimbursement, the total of all such payments is subject to a cap that varies by provider specialty. The payment caps work much like a salary, whereas the fee schedule is based on services actually provided (Busse and Riesberg, 2004). Alternatively, provider characteristics influence payments when fee schedules vary with the provider’s training or specialty. For example, in the United States, a service provided by a doctor is often paid more highly than the same service provided by a nurse or other clinician. A different possibility arises when payment systems reflect not only what services are provided but also who receives them; this corresponds to point E in Figure 1, a payment hybrid of patient and service characteristics. For example, provider fees schedules may vary by insurance plan. In the United States, providers receive different compensation from patients with commercial insurance than from patients with Medicaid coverage. If the payment from commercial insurance exceeds the payment from Medicaid, and if a physician has enough business from commercially insured patients, then the physician has a reduced financial incentive to treat Medicaid patients. Similarly, in Germany, providers receive different compensation from patients in public versus private Sickness Funds. Finally, hybrids corresponding to point F in Figure 1 are also possible, in which some compensation is based on both provider and patient characteristics.

Over the past two decades, payment mechanisms that combine provider, service, and patient characteristics have been developed. Payment systems combining all three of these dimensions are represented by point G in Figure 1. An example is the DRG payment system adopted in many countries, including the United States. In 1983, the U.S. Medicare program began using DRGs to standardize payments and help to control hospital costs. Although many adjustments were made, DRG payments are fixed prices per admission, with the payments reflecting patient characteristics (their diagnoses and age), health services provided (procedure codes), and provider characteristics (type of hospital). Australia, Germany, and several other countries have customized DRGs to their own needs.

At one extreme, point A in Figure 1, payments only depend on the provider’s own characteristics. For example, doctors can be paid a salary regardless of how many or which patients they see and regardless of what services they provide. These salaries may vary by provider characteristics, such as specialty, training, or experience. In many countries, including India and South Africa, public sector doctors are paid a salary. Even in the United States, doctors working for the federal Veterans’ Administration and doctors in certain staff-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are paid a salary. Similarly, in many countries, hospitals receive ‘block grants’; block grants are budgets based on hospital size or type without explicit regard to the number or type of patients seen or the services provided. Many public hospitals, including those in Spain and France, receive fixed annual budgets. Such hospital payment systems invariably adjust for variables such as the numbers of beds or population served, but these are still more correctly thought of as features of the provider and their market rather than patient or service characteristics. For a useful discussion of France’s fixed budget system, see Sauvignet (2005).

Another payment system is represented by point B in Figure 1, in which payments are based solely on the health services provided. Fee-based and cost-based payment systems each pay providers according to the quantity of services given. Payments do not depend on who provides the services or who receives them. Under a fee system providers are paid for each service provided and hence are often called fee-for-service (FFS) payment. Fee payment systems can either allow the provider or the payer to set fee levels. Fee schedules set by the payer are the most common form of reimbursement for doctors; they are used in Canada, Germany, Norway, and the United States. Under a cost-based system, providers may be reimbursed at the end of the year for the cost of inputs (lab material, supplies, and staff salaries) regardless of how these inputs are used. In both cases, if providers use more resources to treat patients, revenues increase.

A third possibility (point C in Figure 1) is that provider payments are based exclusively on patient characteristics. A pure capitation system is a payment system based on patient characteristics. Under capitation, physicians receive a fixed amount of money for each patient they manage. Thus, a physician’s gross income depends on the total number of people he or she cares for; the physician’s income does not depend on the type of provider administering the service, the type of service being provided, or the quantity of services provided. Physician capitation payments were made during the 1990s to general practitioners in the United Kingdom and are used today in the Netherlands (Exter et al., 2004). Similarly, hospitals can be paid according to a pure Diagnostic Related Grouping (DRG) payment system. Under a pure DRG payment system, a hospital receives a fixed amount determined solely by the patient’s diagnostic group. Again, the hospital’s revenue only depends on the patients’ characteristics, not on the provider or service characteristics.

Payment systems are not limited to the three cases corresponding to points A, B, and C; providers can be compensated according to hybrids of different dimensions. Some systems are based on a hybrid of provider and service characteristics, corresponding to point D in Figure 1. The office physician payment system in Germany currently has features that make it appear this way. Although doctors receive FFS reimbursement, the total of all such payments is subject to a cap that varies by provider specialty. The payment caps work much like a salary, whereas the fee schedule is based on services actually provided (Busse and Riesberg, 2004). Alternatively, provider characteristics influence payments when fee schedules vary with the provider’s training or specialty. For example, in the United States, a service provided by a doctor is often paid more highly than the same service provided by a nurse or other clinician. A different possibility arises when payment systems reflect not only what services are provided but also who receives them; this corresponds to point E in Figure 1, a payment hybrid of patient and service characteristics. For example, provider fees schedules may vary by insurance plan. In the United States, providers receive different compensation from patients with commercial insurance than from patients with Medicaid coverage. If the payment from commercial insurance exceeds the payment from Medicaid, and if a physician has enough business from commercially insured patients, then the physician has a reduced financial incentive to treat Medicaid patients. Similarly, in Germany, providers receive different compensation from patients in public versus private Sickness Funds. Finally, hybrids corresponding to point F in Figure 1 are also possible, in which some compensation is based on both provider and patient characteristics.

Over the past two decades, payment mechanisms that combine provider, service, and patient characteristics have been developed. Payment systems combining all three of these dimensions are represented by point G in Figure 1. An example is the DRG payment system adopted in many countries, including the United States. In 1983, the U.S. Medicare program began using DRGs to standardize payments and help to control hospital costs. Although many adjustments were made, DRG payments are fixed prices per admission, with the payments reflecting patient characteristics (their diagnoses and age), health services provided (procedure codes), and provider characteristics (type of hospital). Australia, Germany, and several other countries have customized DRGs to their own needs.

Breadth Of The Payment System

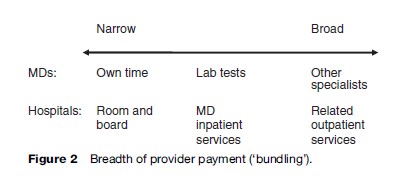

Separate from the issue of the information used to determine the payment system is the issue of how broadly or narrowly provider services are aggregated (Figure 2). Under a narrow system, doctors are paid explicitly for each procedure provided and separate payments are made for each laboratory test or procedure done by other providers. A broader payment system might bundle jointly performed procedures into one fee. A system might broaden even further to include associated fees for laboratory services. A still broader system might make payments to a doctor that include the cost of specialists, forcing the doctor to internalize the cost of all physician services. Similar issues of the breadth of the provider payment system arise with hospital payment. Hospital DRG or per diem rates can narrowly cover only the room and board cost, or may include nursing services. Even more broadly, they may include hospital physician services. In the United States, certain DRG payments have even been broadened to include the cost of services provided after discharge. In some countries hospitals are even given responsibility for certain kinds of primary care services.

This breadth of payments is often discussed in terms of ‘bundling’ of services. Recent trends in the United States have been toward increased bundling of payments. Similar innovations are being tried in many other countries.

Similar issues of the breadth of the provider payment system arise with hospital payment. Hospital DRG or per diem rates can narrowly cover only the room and board cost, or may include nursing services. Even more broadly, they may include hospital physician services. In the United States, certain DRG payments have even been broadened to include the cost of services provided after discharge. In some countries hospitals are even given responsibility for certain kinds of primary care services.

This breadth of payments is often discussed in terms of ‘bundling’ of services. Recent trends in the United States have been toward increased bundling of payments. Similar innovations are being tried in many other countries.

Fineness Of The Payment System

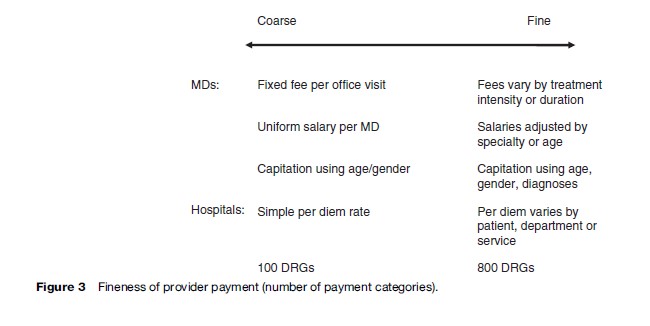

How many payment categories should be used? Should there be many gradations in payment (a ‘fine’ system), or is a simpler (‘coarse’) system appropriate (Figure 3)? In countries such as Taiwan and Korea, physician fee schedules are fairly coarse, with very few fee categories, while physician fee schedules in Australia and the United States are very fine, with many gradations in fee levels. In 2004, Germany reduced the fineness of its fee system. Similar issues of coarseness and fineness arise with DRGs, capitation, and physician salaries. In the United States and many other countries, the DRG and capitation systems have become finer and finer, with increased distinctions made in payments. Coarse or fine gradations in payments are possible with each payment system.

The optimal fineness of the payment system reflects a trade-off between the potentially improved fairness and reduced selection incentives resulting from a fine system and the challenges of monitoring and administering a fine system. Coarser systems should in principle be easier to monitor. If the payer cannot easily distinguish what service was actually provided, or the patient characteristics are not readily observable, then it may not be worthwhile to make such distinctions for payment.

Similar issues of coarseness and fineness arise with DRGs, capitation, and physician salaries. In the United States and many other countries, the DRG and capitation systems have become finer and finer, with increased distinctions made in payments. Coarse or fine gradations in payments are possible with each payment system.

The optimal fineness of the payment system reflects a trade-off between the potentially improved fairness and reduced selection incentives resulting from a fine system and the challenges of monitoring and administering a fine system. Coarser systems should in principle be easier to monitor. If the payer cannot easily distinguish what service was actually provided, or the patient characteristics are not readily observable, then it may not be worthwhile to make such distinctions for payment.