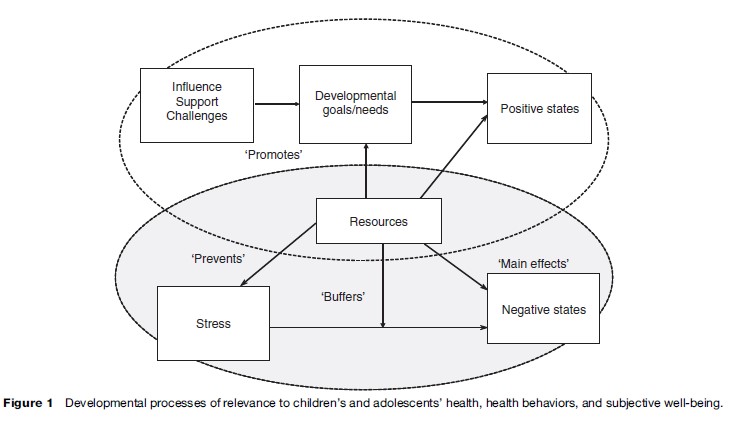

The reason why a whole-school approach is found to be important is that a supportive school environment may be considered a resource for the development of health-enhancing behaviors, health, and subjective wellbeing, while a nonsupportive school environment may constitute a risk. Within this perspective of resource/ risk, students’ satisfaction with school constitutes a key element, as previous research findings suggest a close association between students’ alienation from school and health-compromising behaviors. Subjective well-being among students may be considered a relevant prerequisite for learning in the sense that it allows full concentration on the curricular tasks rather than on coping with distress. Promoting students’ satisfaction with school and their global well-being is a common goal for both educators and health promoters. For both of these groups, students’ satisfaction with school and global well-being are important goals in themselves. On the other hand, educators must also aim at enhancing students’ academic performance. Karasek and Theorell (1990) strongly assert that employers should regard job satisfaction as an important outcome in itself, and not only of interest as a means of increasing productivity. Such a statement is in line with how health promoters evaluate satisfaction with school. Research into adult work environments has identified predictors of both job performance and job satisfaction, and has found that high autonomy and control, adequate demands, and high-level support from colleagues and management are key predictors (Karasek and Theorell, 1990). School may be considered students’ work environment. In this way, concepts from research on adults’ work environments may be relevant to models used to understand how students’ perceptions of school environments relate to their health behaviors and subjective well-being. Positive experiences in the school environment may constitute a resource for academic achievement, satisfaction with school, and global subjective well-being among students (Samdal et al., 1998, 1999). Negative perceptions seem to represent a risk to these positive experiences, and appear to contribute instead to the development of health-compromising behaviors. In either case, the underlying mechanisms can be understood as related to meeting, or failing to meet, basic human needs and goals such as autonomy, social support, and coping with challenges (Ryan and Deci, 2001). Studies have found that student autonomy is the most important facet of students’ psychosocial school environment (Samdal et al., 1998). Furthermore, it is the most important predictor of the dimension of students’ satisfaction with school, which is found to be the key associate of students’ academic achievement (Samdal et al., 1999). This finding corresponds to the results from research into the demand/control model in the adult work environment that indicate that employees can cope with high demands as long as they are given influence on and control in their work practices. In situations of high autonomy (and adequate demands), workers are also less likely to experience strain and depression, and thus higher levels of well-being are anticipated (Karasek and Theorell, 1990). High-level support from fellow students has been found to be the facet of the school environment most strongly related to the subjective well-being of students. This finding corresponds well to research on social relationships, indicating that they may have a direct effect on subjective well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2001). Children and adolescents are in a developmental stage in which relationships with friends become increasingly important. School may therefore provide an important framework for these social relations through the function of providing a daily meeting place. The focus on promoting positive development and experiences as opposed to preventing negative effect of stressful experiences represents in many ways a shift from the traditional public health focus on preventing disease to the new public health focus of promoting health and wellbeing. This shift is illustrated in Figure 1. The gray area represents gravity of present research and traditional focus in public health, whereas the white area suggests topics for future research and focus in new public health.

The traditional public health approach in school has been to identify resources in the psychosocial school environment that could prevent negative outcomes such as health-compromising behaviors, stress, subjective complaints, and mental health problems. Following the one-dimensional view of distress/well-being, the perspective has been that positive experiences in school may prevent stress perceptions and thus reduce negative outcomes and increase positive states. However, when considering recent research findings indicating that there might be different processes leading to negative affect states, new conceptual models are needed to understand the development of positive states as indicated by the white area in Figure 1. In this regard, the fulfillment of developmental goals seems relevant. Processes and activities that stimulate the intrinsically rewarding properties of agency (autonomy) and affiliation (social support) may be of particular interest. In this context, processes and activities taking place in the school setting may be highly relevant.

In the new public health approach, there is still a need to prevent development of health-compromising behaviors such as smoking and to develop health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity and healthy eating. Thus, health promotion in school is both about creating a supportive environment for development and learning, and about the traditional health education approach covered in subjects addressing the cross-curricular topic of health (e.g., physical education, home economics, biology, social science, and religion). With the aim of integrating health promotion into school policy, an important criterion will be to ensure that a systematic approach is taken by the whole school, thus avoiding health promotion in school that is solely dependent upon the individual teacher’s priorities for classroom activities. Part of the health-promotion activities should address long-term and general approaches used year after year, whereas other parts will have to deal with specific issues and problems arising throughout the year.

The traditional public health approach in school has been to identify resources in the psychosocial school environment that could prevent negative outcomes such as health-compromising behaviors, stress, subjective complaints, and mental health problems. Following the one-dimensional view of distress/well-being, the perspective has been that positive experiences in school may prevent stress perceptions and thus reduce negative outcomes and increase positive states. However, when considering recent research findings indicating that there might be different processes leading to negative affect states, new conceptual models are needed to understand the development of positive states as indicated by the white area in Figure 1. In this regard, the fulfillment of developmental goals seems relevant. Processes and activities that stimulate the intrinsically rewarding properties of agency (autonomy) and affiliation (social support) may be of particular interest. In this context, processes and activities taking place in the school setting may be highly relevant.

In the new public health approach, there is still a need to prevent development of health-compromising behaviors such as smoking and to develop health-promoting behaviors such as physical activity and healthy eating. Thus, health promotion in school is both about creating a supportive environment for development and learning, and about the traditional health education approach covered in subjects addressing the cross-curricular topic of health (e.g., physical education, home economics, biology, social science, and religion). With the aim of integrating health promotion into school policy, an important criterion will be to ensure that a systematic approach is taken by the whole school, thus avoiding health promotion in school that is solely dependent upon the individual teacher’s priorities for classroom activities. Part of the health-promotion activities should address long-term and general approaches used year after year, whereas other parts will have to deal with specific issues and problems arising throughout the year.