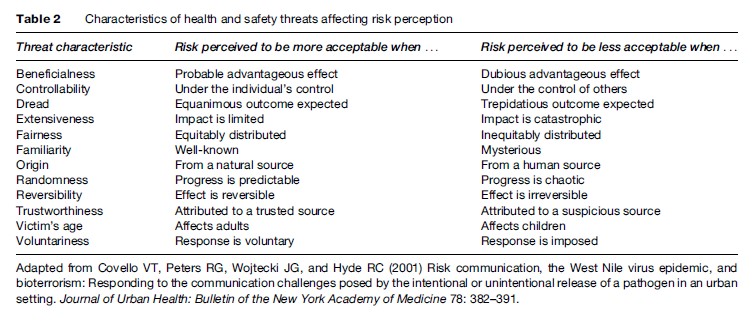

A growing interdisciplinary literature informs our understanding of how individuals perceive and respond to public health risk communication. In particular, research has focused on the cognitive mechanisms through which individuals are exposed to and attend to information about risk, how they interpret risk information in relation to themselves, and whether and how they act upon risk information to enact self-protective behaviors. Risk perception, defined as the subjective assessment or judgment of a threat, has emerged as a key concept. Indeed, risk perception, not the actual risk posed by a threat, seems the primary factor guiding cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions elicited when conditions challenge an individual’s health and safety. Lay and technical audiences, for instance, often perceive risk estimates quite differently. Consider a circumstance in which public health officials innumerate the likelihood of a health risk as 1 in 1000. Health experts understand this estimate in terms of relative risk; one person in every 1000 people is at risk. For the public, however, such estimates are commonly misinterpreted. Nontechnical audiences, in particular, tend to personalize health assessments, and their perceptions of risk often are distorted by an emotional bias emanating from concerns that individuals close to them are at significant risk. A range of factors has been identified that mediate risk perception. Specific characteristics of health or safety threats, for example, can influence how risks are perceived. Some of these characteristics, along with attributes shaping the directionality of perceived risk, are presented in Table 2. As an illustration, consider a health communication campaign, targeted at parents of asthmatic children, promoting home environment exposure-management awareness. Articulating multifaceted approaches involving direct actions (e.g., using dust-mite-impermeable bedcovers, avoiding tobacco smoke, damp-mopping hard surfaces) that parents can control, that they can voluntarily implement, and that predictably yield beneficial effects (National Institutes of Health, 2007) should help lower their perceptions of home environment asthma risks. Similarly, several social and psychological factors appear to diminish individuals’ comprehension of scientific or probabilistic information about risks to health and safety. For example, while elevated risk perceptions can sometimes promote proactive protective behaviors, they can also produce an unintended consequence: a contradictory effect engendering negative emotional reactions and creating resistance to health-protective recommendations and other risk-reduction messages.

Theoretical Diversity In Public Health Risk Communication

Strategies for overcoming social and psychological barriers to effective public health risk communication emerge from a number of theoretical perspectives. The mental models approach (Morgan et al., 2002), for example, offers tools for better understanding how a lay audience’s cognitive beliefs about medical and environmental risks impact their interpretations of health risk messages and outlines specific ways in which technical and scientific concepts can be tailored and focused into understandable risk communication. Specifically, the mental models approach involves a five-step method for creating and testing risk messages. The first step involves creation and analysis of an ‘expert model,’ which is depicted as an influence diagram, summarizing scientific evidence and expert opinion about a health threat. In step two, open-ended interviews of lay respondents assessing their beliefs about the health threat are undertaken to determine the external validity of the expert model. A confirmatory questionnaire, built upon information gleaned in the first two steps, is administered in step three to a large sample from the anticipated target audience in order to establish the population prevalence of health-threat beliefs. In step four, based on the accumulated results, risk communication messages designed to enhance awareness of and correct distorted beliefs about the health threat are developed and subjected to expert scrutiny. Further refinement of the health-threat risk communication messages using various evaluative research methods is the focus of step five. Growing evidence suggests that the mental models approach, when properly used, can yield clear and understandable messages about health risks. Concepts from the health belief model ( Janz et al., 2002) can also inform public health risk communication practice. Within this framework, people are seen as engaging in self-protective actions to reduce health risk exposure if they believe they are vulnerable, believe that such actions will beneficially reduce their risk susceptibility, and believe that the barriers (or costs) of self-protective action are exceeded by the perceived benefits. Protection motivation theory, stages of change models, and other promising concepts (i.e., mental noise, negative dominance, and trust determination) have also informed public health risk communication practice.Emerging Trends In Public Health Risk Communication

Advancements in our understanding of factors that can maximize the effectiveness of public health risk communication principles and practices continue throughout the behavioral, health, and social sciences. One emerging trend in public health risk communication is the development and implementation of effective individual-level risk communication strategies and messages. Although science-based evidence about the risk factors associated with chronic diseases and ill health has grown substantially, realization of the full benefits of this actionable knowledge can occur only when effective interventions are identified and when health professionals become proficient risk communicators. A number of recent systematic reviews illustrate, in fact, considerable efficacy of risk communication interventions (e.g., improving women’s health and outcomes following genetic testing and counseling) in clinical health practice settings (Edwards et al., 2000; Rowe et al., 2002; Butow et al., 2003). What to do about the Internet and other new ‘communication technologies’ also remains an emerging issue facing public health risk communicators. Undoubtedly, the Internet offers a highly efficient channel for rapid dissemination of health and safety risk information. Effectively integrating the Internet into emergency response communication plans remains a challenge, however. Events surrounding the April 16, 2007, tragedy on the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University campus in the U.S. provide a vivid example. Following an early morning double-murder shooting in a campus dormitory, university officials relied primarily on e-mails to disseminate warning and advisory news and information to the university community. The initial notification, emailed over 2 h after the attack and several min after the day’s classes had begun, informed of an ongoing homicide investigation, urged vigilance and caution, and directed students and employees to a website for further updates. Only moments later, the deadliest shooting rampage on a U.S. university campus began. In this instance, the delayed timing of the Internet notification, the transitory nature of the target audience and, consequently, their limited e-mail access, and the dynamic nature of the emergency converged, essentially mitigating the effectiveness of the risk communication effort. Finally, an emerging focus area where considerable progress is evident involves the practice of public health risk communication during crisis or emergency events. Crisis and emergency risk communication (CERC; Reynolds and Seeger, 2005), for example, is a systematic approach to catastrophe-bound public health risk communication that is broader and more comprehensive than traditional models. Foundational to the CERC framework is recognition that crisis and emergency events, while unpredictable, typically evolve through unique developmental stages, from pre-crisis to initial event through maintenance to resolution and on to evaluation. By projecting emergency events as developing in an orderly and sequential progressive manner, CERC promotes strategic anticipation of the information demands and exigencies of affected audiences during each catastrophe stage and highlights the essential preparatory work and event-bound practices necessary to satisfy anticipated risk communication needs. Bibliography:- Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry (2007) A Primer on Health Risk Communication: Principles and Practices. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http:// www.atsdr.cdc.gov/risk/riskprimer/index.html (accessed November 2007).