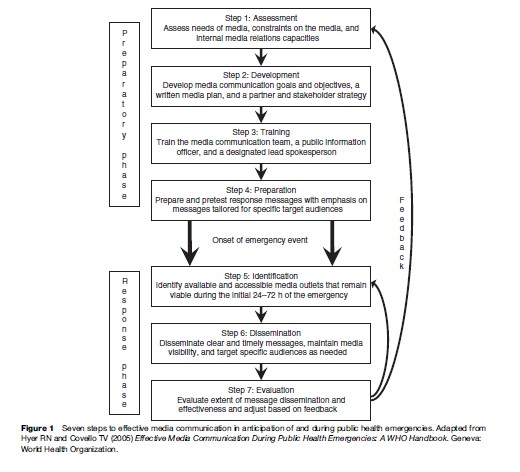

Equally important is recognition of the pivotal role frequently played by the mass media in distributing public health risk communication messages and, consequently, their potential influence on subsequent events. This fact is emphasized by the range of major public health organizations (e.g., Thesenvitz, 2000; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2002; World Health Organization, 2005; Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry, 2007; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007) that have published extensive guidelines and recommendations for involvement of the media during crises and emergencies. The World Health Organization handbook, Effective Media Communication During Public Health Emergencies (Hyder and Covello, 2005), offers a particularly comprehensive summary organized around a seven-step model. This model of effective media communication during public health emergencies is illustrated in Figure 1. As can be seen, the first four steps of the model detail ongoing preparatory activities (i.e., needs assessment, strategy development, response training, and message preparation) that public health risk communicators should undertake in anticipation of a potential emergency. The next two steps – identification of accessible media outlets and execution of message dissemination plans – are initiated once an emergency event is forthcoming or is rapidly evolving. The seventh step is evaluation. As illustrated in Figure 1, the evaluation step involves two feedback loops, indicating that evaluative activities should occur both as an ongoing activity during the emergency and, more substantially, following resolution of the event.

The necessity for public health risk communicators to evaluate continually the role played by mass media during an emergency was demonstrated during the 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Katrina, which devastated coastal areas of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Essentially all strategic hurricane response planning for the region heavily involved traditional electronic media (e.g., radio and television broadcast stations and cable television systems) and emerging technologies (e.g., e-mail) as the primary emergency information dissemination channels. The magnitude of storm damage and subsequent flooding, however, virtually silenced all of these media, forcing public health risk communicators to seek alternative channels. Risk communication specialists in the Joint Information Center at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta quickly recognized that the planned channels for message dissemination were inaccessible and turned to alternative mechanisms. Within days, for example, crucial health protective messages, printed in Atlanta and trucked to devastated areas, began reaching many of the most affected victims. Then, in the ensuing weeks, CDC staff who were deployed just outside the worst affected areas used the Internet and local facilities to print materials that were circulated among storm survivors at reentry and evacuation points, food and ice distribution centers, and door to door.

The necessity for public health risk communicators to evaluate continually the role played by mass media during an emergency was demonstrated during the 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Katrina, which devastated coastal areas of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Essentially all strategic hurricane response planning for the region heavily involved traditional electronic media (e.g., radio and television broadcast stations and cable television systems) and emerging technologies (e.g., e-mail) as the primary emergency information dissemination channels. The magnitude of storm damage and subsequent flooding, however, virtually silenced all of these media, forcing public health risk communicators to seek alternative channels. Risk communication specialists in the Joint Information Center at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta quickly recognized that the planned channels for message dissemination were inaccessible and turned to alternative mechanisms. Within days, for example, crucial health protective messages, printed in Atlanta and trucked to devastated areas, began reaching many of the most affected victims. Then, in the ensuing weeks, CDC staff who were deployed just outside the worst affected areas used the Internet and local facilities to print materials that were circulated among storm survivors at reentry and evacuation points, food and ice distribution centers, and door to door.