In general, there are three possible factors to consider in the perception, attribution, and reporting of racism: (1) overestimation due to system blame, external attribution, or aspects of identity or social position/context that may lead to enhanced vigilance, hypersensitivity, etc.; (2) underestimation due to internalized racism, internal attribution, or aspects of identity or social position/ context that may preclude recognition or conscious awareness of racism (or produce skewed notions of fair treatment); and (3) cognitive/affective and methodological factors such as domain priming (i.e., the explicit use of race terminology) or social desirability bias that can either increase or decrease the perception, attribution, and reporting of racism. In relation to overestimation, there is some evidence that a heightened sense of ethnoracial identity is associated with increased reporting of racism. However, this may only be the case for members of minority ethnoracial groups rather than for Whites and may occur only for ambiguous rather than blatant racist incidents. The relationship between reporting of racism and ethnoracial identity is bidirectional with many studies showing that minority ethnoracial group members who recognize more racism against their ethnoracial group have strengthened ethnoracial identification. Furthermore, a stronger identity may predispose individuals to experiencing (as well as perceiving and reporting) more racism through the way they interact with others. Although there has been far less research conducted on aspects of underestimation, there is preliminary evidence that internalized racism is associated with less perceived racism after adjustment for ethnoracial identity. The explicit use of race terminology (rather than questions on discrimination in general which are later attributed to ethnorace) appears to increase reports of racism, perhaps by prompting respondents to assign racial meaning to ambiguous negative events. Another phenomenon that sheds light on the cognitive factors involved in reporting racism is the person–group discrimination discrepancy (PGDD). The PGDD describes the well-established tendency for individuals to report that their ethnoracial group is exposed to more racism than they are personally. There is evidence that the PGDD occurs when respondents determine the extent of personal discrimination through comparison with other members of their own ethnoracial group while determining the extent of group discrimination in comparison to other ethnoracial groups. The use of different standards of comparison (which may result in this ‘discrepancy’) raises broader questions about the cognitive processes involved in reporting racism. Other research has demonstrated that self-reported racism is not related to neuroticism, hostility, cynicism, social desirability, or impression management. Conversely, reports of racism have been found to relate inversely to both self-deception (i.e,. a pervasive lack of insight) and self-affirmation. Moreover, as noted by Clark (2004), it is not known to what extent individuals habituate to experiences of racism and how this affects processes that may be related to health and well-being. In the context of such difficulties in operationalizing racism, the next section considers the ways in which racism can be characterized as a determinant of health.

Characterizing Racism

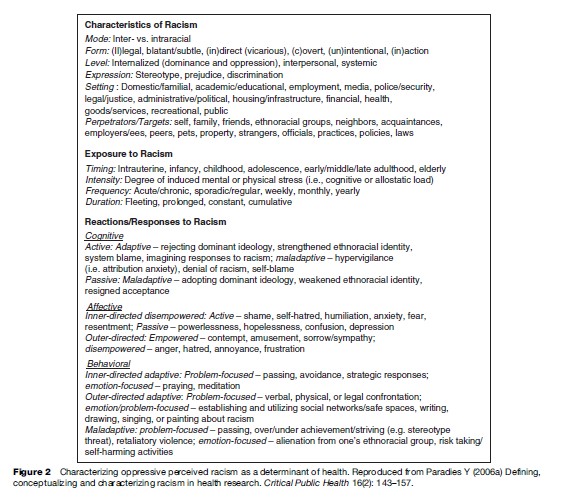

To date, the vast majority of research on racism and health has focused on perceived racism (and, more specifically, perceived racial discrimination). Figure 2 details the range of dimensions across which perceived racism has been characterized in health research, including dimensions of exposure to racism as well as possible reactions and responses to this exposure. As discussed previously, racism can be due to either oppression or privilege. However, virtually no research has been conducted in relation to racism as privilege and its association with health. As a result, the characterization of racism in Figure 2 (and as discussed later) relates only to the oppressive aspects of perceived racism. The characteristics of racism include its mode, form, level, expression, and setting as well as its perpetrators and targets. Racism can take a variety of forms including legal or illegal, direct or indirect, overt or covert, blatant or subtle, as well as vicarious by way of other targets of racism such as family or friends. Racism can also be unintentional as well as intentional and may occur through both action and inaction.

Some scholars contend that racism can occur between individuals of the same ethnorace (intraracially) as well as between individuals of different ethnoraces (interracially). However, there is continuing debate in this field as to whether intraracial racism should be accepted as a form of racism. Although some argue that members of minority ethnoracial groups lack the power to be racist, it is well established that minority group members discriminate against each other on the basis of racial characteristics such as skin color, and it is probable that such behavior affects the social power of those targeted. While very little research has examined intraracial racism, there is preliminary evidence of its deleterious effect on health.

Racism can be expressed through stereotypes, prejudice, or discrimination – that is, racist beliefs (cognition), emotions (affect), and behaviors, respectively – in a range of settings that correspond to the institutions represented in the structural realm of Figure 1. There is also a range of possible perpetrators or targets of racism, some of which are shown in Figure 2. Exposure to racism can occur at different stages of the life course with varying frequency at a range of intensities in relation to mental or physical stress. The duration of exposure to racism can also vary from fleeting to constant and can occur cumulatively across settings or over time.

Reactions/responses to racism may be cognitive, affective, or behavioral and in active or passive as well as adaptive or maladaptive forms. Self-blame is a cognitive, active, maladaptive response that occurs when a racist experience is given an internal attribution by an individual (i.e., through self-blame). In contrast, the cognitive, active, adaptive response of system-blame occurs when a racist experience is given an attribution external to the self. Another cognitive, maladaptive, active response to racism is hypervigilance in which an individual devotes an extreme amount of cognitive effort to anticipating racism, attempting to prevent racism, or in determining whether racism has occurred. This coping response can result in additional stress above and beyond the direct effects of racism itself. ‘Denial of racism’ and ‘self-blame’ (active responses) and ‘resigned acceptance’ (passive response) are cognitive responses that negate the need to process experiences of racism at all.

The characteristics of racism include its mode, form, level, expression, and setting as well as its perpetrators and targets. Racism can take a variety of forms including legal or illegal, direct or indirect, overt or covert, blatant or subtle, as well as vicarious by way of other targets of racism such as family or friends. Racism can also be unintentional as well as intentional and may occur through both action and inaction.

Some scholars contend that racism can occur between individuals of the same ethnorace (intraracially) as well as between individuals of different ethnoraces (interracially). However, there is continuing debate in this field as to whether intraracial racism should be accepted as a form of racism. Although some argue that members of minority ethnoracial groups lack the power to be racist, it is well established that minority group members discriminate against each other on the basis of racial characteristics such as skin color, and it is probable that such behavior affects the social power of those targeted. While very little research has examined intraracial racism, there is preliminary evidence of its deleterious effect on health.

Racism can be expressed through stereotypes, prejudice, or discrimination – that is, racist beliefs (cognition), emotions (affect), and behaviors, respectively – in a range of settings that correspond to the institutions represented in the structural realm of Figure 1. There is also a range of possible perpetrators or targets of racism, some of which are shown in Figure 2. Exposure to racism can occur at different stages of the life course with varying frequency at a range of intensities in relation to mental or physical stress. The duration of exposure to racism can also vary from fleeting to constant and can occur cumulatively across settings or over time.

Reactions/responses to racism may be cognitive, affective, or behavioral and in active or passive as well as adaptive or maladaptive forms. Self-blame is a cognitive, active, maladaptive response that occurs when a racist experience is given an internal attribution by an individual (i.e., through self-blame). In contrast, the cognitive, active, adaptive response of system-blame occurs when a racist experience is given an attribution external to the self. Another cognitive, maladaptive, active response to racism is hypervigilance in which an individual devotes an extreme amount of cognitive effort to anticipating racism, attempting to prevent racism, or in determining whether racism has occurred. This coping response can result in additional stress above and beyond the direct effects of racism itself. ‘Denial of racism’ and ‘self-blame’ (active responses) and ‘resigned acceptance’ (passive response) are cognitive responses that negate the need to process experiences of racism at all.