The pretransition health-care system in the former Soviet Union, also known as the Semashko model (Nikolai Semashko (1874–1949) was a member of the Bolshevik Party who became USSR’s People’s Commissar of Public Health in 1923 and was instrumental in setting up the Soviet model of health care.), sought to provide universal access through an extensive network of facilities and was among the most visible achievements of the USSR. Evidence on system functioning and health outcomes predating the end of the communist regime is limited, but there are indications that, at least formally, the health systems shared considerable uniformity.

Before the Russian Revolution, health care in rural areas was extremely limited, with some provision by local government and charitable donations. Living conditions and health in many remote areas remained very poor. Following the revolution, public health became a political priority because the poor health of the population was seen as endangering the success of the revolution, with the already high death rates increased further by epidemics of communicable diseases.

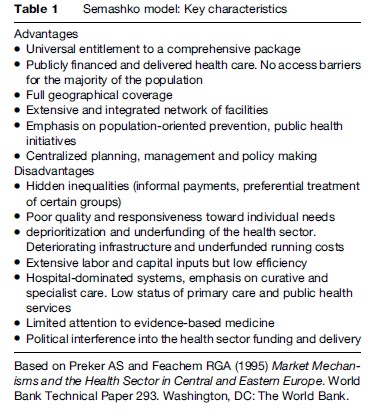

The basic elements of a health-care system in the USSR began to be put in place in the 1920s. These reforms accelerated during the late 1940s and 1950s through the establishment of a network of facilities that reached out into the most remote settlements, providing basic coverage to almost the entire population. The Soviet-style health-care model was replicated throughout Central and Eastern Europe after the Second World War. The health-care systems were publicly financed, through general taxation, with the state owning the facilities and providing all health services (Table 1). Access to care was free at the point of use. The formal private sector was nonexistent. The system was labor-intensive, largely because it was possible to keep the wages of health professionals in the health sector low when the state was the monopoly employer. In Russia, the health-care system focused in particular on mothers and children and the control of infectious diseases, reflecting the importance given to boosting population growth. Infant and maternal mortality fell rapidly, in part due to the expanded healthcare system but also because of achievements in other sectors, such as nearly full employment and improved living conditions, albeit achievements made at a huge human cost, with those who stood in the way of progress being sent to the gulag. Inevitably, the quality of care varied; it was always better in the cities than in villages. But compared to what had existed before, for most people it was a considerable improvement.

Before the Russian Revolution, health care in rural areas was extremely limited, with some provision by local government and charitable donations. Living conditions and health in many remote areas remained very poor. Following the revolution, public health became a political priority because the poor health of the population was seen as endangering the success of the revolution, with the already high death rates increased further by epidemics of communicable diseases.

The basic elements of a health-care system in the USSR began to be put in place in the 1920s. These reforms accelerated during the late 1940s and 1950s through the establishment of a network of facilities that reached out into the most remote settlements, providing basic coverage to almost the entire population. The Soviet-style health-care model was replicated throughout Central and Eastern Europe after the Second World War. The health-care systems were publicly financed, through general taxation, with the state owning the facilities and providing all health services (Table 1). Access to care was free at the point of use. The formal private sector was nonexistent. The system was labor-intensive, largely because it was possible to keep the wages of health professionals in the health sector low when the state was the monopoly employer. In Russia, the health-care system focused in particular on mothers and children and the control of infectious diseases, reflecting the importance given to boosting population growth. Infant and maternal mortality fell rapidly, in part due to the expanded healthcare system but also because of achievements in other sectors, such as nearly full employment and improved living conditions, albeit achievements made at a huge human cost, with those who stood in the way of progress being sent to the gulag. Inevitably, the quality of care varied; it was always better in the cities than in villages. But compared to what had existed before, for most people it was a considerable improvement.

Health systems were both integrated and vertically structured, with precisely defined responsibilities for each level of care. Services were provided through extensive networks of facilities covering designated catchment areas. The primary care level consisted of polyclinics (and subordinate rural ambulatories) typically staffed by district physicians and several specialists with basic training. Rural ambulatories and health posts often employed feldshers or community-based health workers who often served state collective farms. Primary care facilities were subordinated to district-level and regional hospitals for secondary care and referral institutes for tertiary care. While polyclinic care was relatively accessible, with free access to local providers, obtaining treatment at higher-level institutions may have been dependent on patronage and informal payments, although data is anecdotal. However, the health-care system had a strong hospital-based and specialist care orientation, since primary care providers had only basic skills and equipment and did not function as gatekeepers (indeed incentives to refer existed).

There were also separate specialist structures, for example dispensaries, which ran vertical disease control programs dedicated to sexually transmitted diseases, mental health, tuberculosis, cancer, etc. These were in addition to sanitary-epidemiological stations responsible for public health initiatives, licensing of institutions, and infectious diseases surveillance. These had separate management structures and information systems. There were also parallel services for people working in the defense industries and the military, transport sector, penitentiary systems, and others.

The system was centrally planned and usually national or regional levels of state administration were responsible for management, resource allocation, and regulation. In Russia, the health system was regulated by a Ministry of Health and its branches at republican and regional level, through a centralized system of decrees (in Russia prikaz) enacted nationally, regulating mainly the structure of the health system, providing norms for staffing, facilities, and operational procedures such as frequency of visits and procedures (e.g., prenatal visits, blood tests). The Ministry of Health prikazes also set treatment standards, although these were often vague and provided general guidance rather than specific directions for clinical care and were often based on advice from leading specialists and traditions rather than upon the emerging internationally accepted paradigm of evidence-based medicine.

Health sector financing was determined on a residual basis (after the needs of other sectors had been met) and was below that of other industrialized countries, at 4% of GDP on average in the 1990s compared to the OECD average of over 6%. Furthermore, resource allocation of inefficient, based on fixed norms for the number of staff and beds per population, on a historical basis, and not taking into account volumes or quality of clinical activity or public health impact. These regulatory and financing arrangements led to a continuing overmedicalization of the health system.

Even during the communist era, access to good-quality care was increasingly inequitable. Members of the Communist Party elite, as well as sectors with parallel health systems, such as the military and employees of some state industries, had privileged access to care and pharmaceuticals that were of much higher quality than the average. There are indications that access to good-quality care was dependent on the use of connections or offering gifts. However, the formal entitlement to service was still in existence and was (and remains) clearly stated in the constitutions of most countries. The system could not support interventions that were becoming increasingly available in the West, in part because of lack of funds but also because of restrictions on imports from Western countries that were concerned about the use of advanced technology for military purposes.

By the late 1980s, the system was struggling to respond to the needs of the population and was becoming increasingly ineffective, inefficient, and obsolete (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006) After 1991, in many places the system collapsed in the face of serious financial shortages, triggering a huge increase in out-of-pocket payments, and reducing coverage of essential interventions.

Health systems were both integrated and vertically structured, with precisely defined responsibilities for each level of care. Services were provided through extensive networks of facilities covering designated catchment areas. The primary care level consisted of polyclinics (and subordinate rural ambulatories) typically staffed by district physicians and several specialists with basic training. Rural ambulatories and health posts often employed feldshers or community-based health workers who often served state collective farms. Primary care facilities were subordinated to district-level and regional hospitals for secondary care and referral institutes for tertiary care. While polyclinic care was relatively accessible, with free access to local providers, obtaining treatment at higher-level institutions may have been dependent on patronage and informal payments, although data is anecdotal. However, the health-care system had a strong hospital-based and specialist care orientation, since primary care providers had only basic skills and equipment and did not function as gatekeepers (indeed incentives to refer existed).

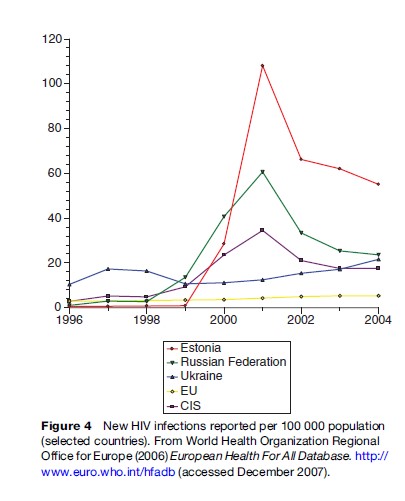

There were also separate specialist structures, for example dispensaries, which ran vertical disease control programs dedicated to sexually transmitted diseases, mental health, tuberculosis, cancer, etc. These were in addition to sanitary-epidemiological stations responsible for public health initiatives, licensing of institutions, and infectious diseases surveillance. These had separate management structures and information systems. There were also parallel services for people working in the defense industries and the military, transport sector, penitentiary systems, and others.

The system was centrally planned and usually national or regional levels of state administration were responsible for management, resource allocation, and regulation. In Russia, the health system was regulated by a Ministry of Health and its branches at republican and regional level, through a centralized system of decrees (in Russia prikaz) enacted nationally, regulating mainly the structure of the health system, providing norms for staffing, facilities, and operational procedures such as frequency of visits and procedures (e.g., prenatal visits, blood tests). The Ministry of Health prikazes also set treatment standards, although these were often vague and provided general guidance rather than specific directions for clinical care and were often based on advice from leading specialists and traditions rather than upon the emerging internationally accepted paradigm of evidence-based medicine.

Health sector financing was determined on a residual basis (after the needs of other sectors had been met) and was below that of other industrialized countries, at 4% of GDP on average in the 1990s compared to the OECD average of over 6%. Furthermore, resource allocation of inefficient, based on fixed norms for the number of staff and beds per population, on a historical basis, and not taking into account volumes or quality of clinical activity or public health impact. These regulatory and financing arrangements led to a continuing overmedicalization of the health system.

Even during the communist era, access to good-quality care was increasingly inequitable. Members of the Communist Party elite, as well as sectors with parallel health systems, such as the military and employees of some state industries, had privileged access to care and pharmaceuticals that were of much higher quality than the average. There are indications that access to good-quality care was dependent on the use of connections or offering gifts. However, the formal entitlement to service was still in existence and was (and remains) clearly stated in the constitutions of most countries. The system could not support interventions that were becoming increasingly available in the West, in part because of lack of funds but also because of restrictions on imports from Western countries that were concerned about the use of advanced technology for military purposes.

By the late 1980s, the system was struggling to respond to the needs of the population and was becoming increasingly ineffective, inefficient, and obsolete (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2006) After 1991, in many places the system collapsed in the face of serious financial shortages, triggering a huge increase in out-of-pocket payments, and reducing coverage of essential interventions.