Malaria And HIV Co-Infection

Current evidence supports that HIV and malaria each negatively affect the outcome and course of the other. It has been suggested that HIV-related immune suppression compromises innate host malaria clearance mechanisms. In regions where malaria transmission is low or unstable, HIV-positive adults with malaria are two to fivefold more likely to have a complicated or severe course. HIV has also been shown to impair the response to antimalarial therapy, with higher rates of treatment failure among those who are co-infected. Malaria has been shown to upregulate HIV transcription, with those who are co-infected demonstrating a two to sevenfold increase in HIV viral load during acute malaria infection. Whether this acute rise in viremia is clinically significant is debatable. However, at least one study in Uganda has shown a significant decline in CD4 counts in HIV-positive patients following episodes of malaria.

Management

There are three cardinal questions that must be addressed for optimal management of malaria:

- Is the infection caused by P. falciparum?

- Is the malaria complicated or severe?

- Is the parasite likely to be drug-resistant?

The answers to these questions will greatly influence the decisions made in managing these patients.

Is The Infection Caused By P. Falciparum?

Species identification of the infecting organism is critical to appropriate management. P. falciparum can cause life-threatening disease in nonimmune adults and children, and should be considered a medical emergency. The clinical descent down the slope of severe manifestations can be rapid; therefore, prompt initiation of therapy is essential. While the management objectives for P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale are to cure disease and, in the case of P. vivax and P. ovale, to prevent relapse, because P. falciparum can cause fatal disease, its treatment objectives are to cure disease and to prevent death. Thick and thin Giemsa-stained blood smears allow for species identification and quantification of parasitemia. Point-of-care speciation is also available through use of sensitive rapid dipstick assays, which detect P. falciparum antigens such as HRP-2. While molecular assays also permit speciation, as yet, their turnaround times are prohibitive for point-ofcare diagnostics.

Is The Malaria Complicated Or Severe?

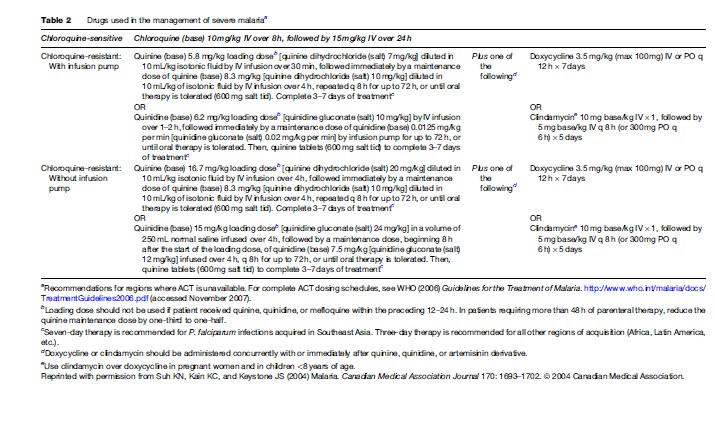

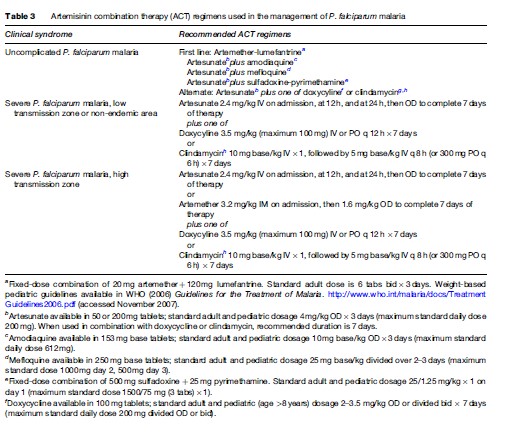

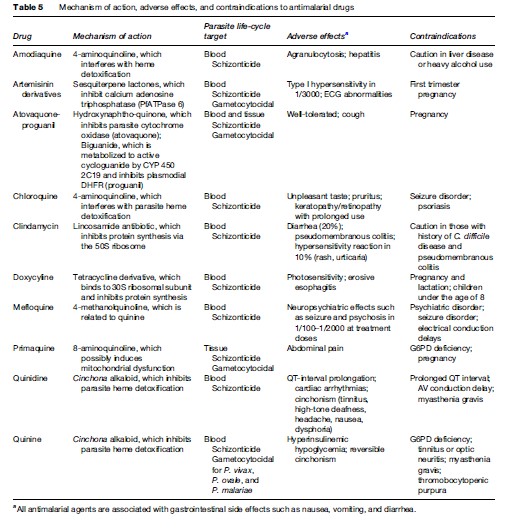

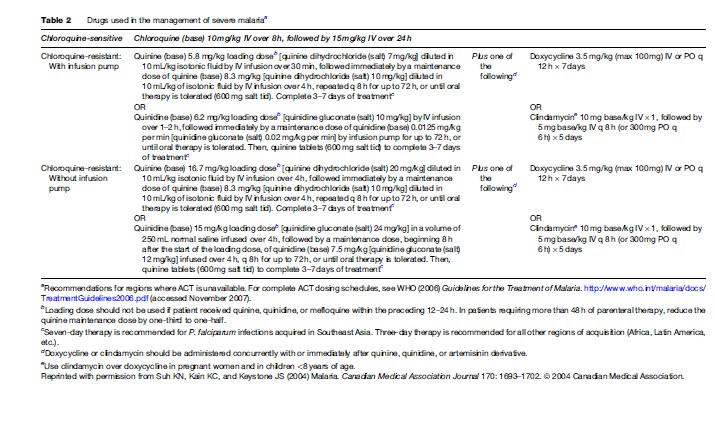

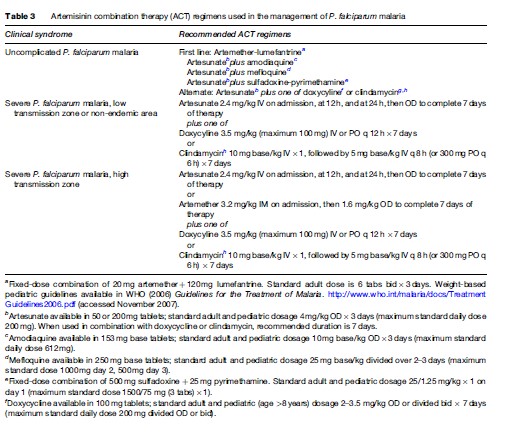

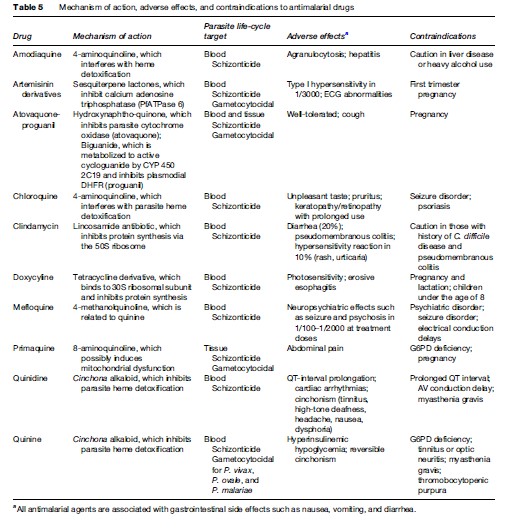

Severe or cerebral malaria necessitates immediate administration of combination parenteral antimalarials (Table 2) and ongoing supportive care. Artemisinin derivatives are the most potent antimalarials known to man, and are derived from the leaves of the Artemisia annua plant. Artemisinin combination therapy (ACT), which pairs an artemisinin derivative with another antimalarial drug, is recommended by the WHO for management of all P. falciparum malaria, whether severe or not, in areas where these drugs are available. However, the lack of availability of ACT in many Western countries limits its use predominantly to endemic areas in Africa and Southeast Asia. The choice of therapy will also therefore depend on location and local formularies. Table 2 summarizes the current recommendations for therapy of severe P. falciparum malaria in areas where ACT is unavailable. Table 3 lists the currently recommended ACT regimens for P. falciparum malaria. A comprehensive discussion of ACT dosing schedules and practicalities of administration can be found in the 2006 WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria. Oral therapy alone, while indicated for uncomplicated malaria (Table 4), is inadequate in the setting of severe disease, or in patients who are vomiting. Adverse effects and contraindications to currently used antimalarials are listed in Table 5. Vigilant patient monitoring in an ICU setting is ideal, with particular attention paid to vital signs, glycemia (accuchecks q 2–4 h), neurologic status, arterial blood gas, urine output, and parasitemia.

Fluid therapy in the context of severe malaria remains controversial, and must be assessed on an individual basis. A balance must be struck between the risk of fluid overload, to which adults with severe disease are particularly vulnerable, and dehydration, which will necessarily worsen concomitant renal failure. Children with severe malaria are more likely than adults to be volume depleted, and may respond favourably to a fluid bolus. The hyperventilation and respiratory distress seen in children with severe malaria is attributable to metabolic acidosis and severe anemia. Blood transfusion is therefore indicated in children with hemoglobin <50 g/L (<5 g/dl) who are from high-transmission zones. A more conservative threshold for transfusion of hemoglobin, <70 g/L (<7 g/dl), can be applied to those with severe anemia who reside in low-transmission zones or are residents of the developed world who have returned from travel to an endemic area.

Acute pulmonary edema should be managed as per standard of care with supplemental oxygen, positive pressure ventilation if available and the patient is hypoxic, and therapeutic maneuvers that reduce preload on the heart, including diuresis, venodilation, hemofiltration, and dialysis. In patients with significant coagulopathy, vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma can be given. Correction of hypovolemia and anemia are key to ameliorating metabolic acidosis. To date, no other intervention has proven valuable.

Seizures are a common complication of cerebral malaria, especially in children. Administration of intravenous benzodiazepines is the mainstay of treatment of seizures due to cerebral malaria. The WHO currently recommends against use of phenobarbital in children with malarial seizures, due to its association with increased mortality (WHO, 2006). Preemptive administration of antiseizure medication is not recommended.

Hyperparasitemia is a major risk factor for death from severe malaria. Parasitemia should therefore be followed every 6–12 h over the first 24–48 h of therapy. In addition to parenteral antimalarials, exchange transfusion or aphoresis has been touted as an effective way to reduce parasite burden, though evidence to support this maneuver is scant and it thus remains controversial. Its use should probably be limited to situations in which prognosis is grave, parasitemia is >30%, or parasitemia is >10% with accompanying evidence of end-organ dysfunction including cerebral, pulmonary, or renal manifestations.

The continued high rate of mortality in severe and cerebral malaria has led to the investigation of a number of adjuvant therapies for P. falciparum malaria including corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies to TNFa, TNFa inhibitors, heparin, prostacyclin, and desferroxamine. None of these adjuvant therapies has proven efficacious in clinical trials, and therefore none is recommended.

In cases of severe malaria, where presentation is that of a systemic febrile illness with evidence of multisystem involvement, the concurrent use of parenteral broadspectrum antibiotics should be liberal. Intercurrent bacterial infection is common, particularly in children, and may be overshadowed by the diagnosis of malaria. Thus, this entity must be anticipated, especially in the setting of unexplained deterioration despite effective antimalarial and supportive therapy.

Because P. falciparum infection in pregnancy is associated with low birth weight, adverse fetal outcome, severe maternal anemia, and increased risk of severe sequelae, particularly pulmonary edema and hypoglycemia, administration of antimalarial therapy must not be delayed. Prompt initiation of parenteral therapy is indicated in pregnant women with severe malaria. In later stages of pregnancy, artesunate may be preferred over quinine due to the latter’s association with recurrent hypoglycemia.

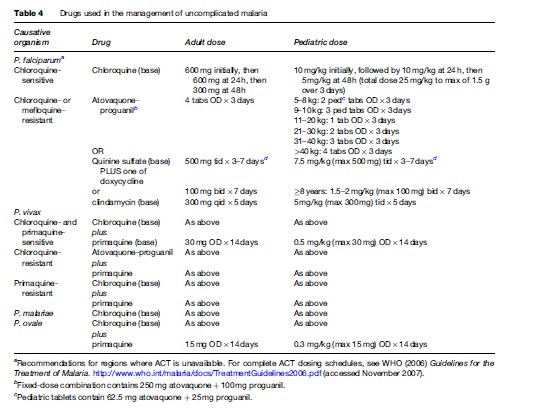

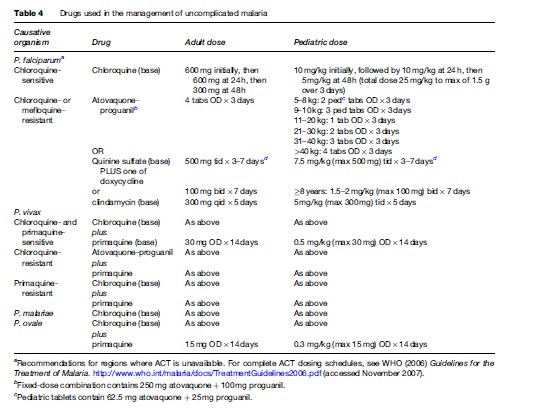

Pharmacotherapy of uncomplicated malaria is summarized in Table 4. Unless a patient cannot tolerate oral medication due to vomiting or is believed to have poor gastrointestinal absorption, therapy of uncomplicated malaria should be via the oral route. Outside of Africa, P. vivax is the predominant species causing disease. P. vivax and P. ovale have a persistent liver phase that is responsible for clinical relapses. In order to reduce the risk of relapse following the treatment of symptomatic P. vivax or P. ovale infection, primaquine may be indicated to provide ‘radical cure.’ Primaquine use is contraindicated in pregnancy; therefore, P. vivax and P. ovale infections occurring during pregnancy should be treated with standard doses of chloroquine. Relapses can then be prevented by weekly chemosuppression with chloroquine until after delivery. Because of primaquine’s oxidant hemolytic potential, patients should undergo testing for glucose-6phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency prior to initiation of primaquine therapy.

Fluid therapy in the context of severe malaria remains controversial, and must be assessed on an individual basis. A balance must be struck between the risk of fluid overload, to which adults with severe disease are particularly vulnerable, and dehydration, which will necessarily worsen concomitant renal failure. Children with severe malaria are more likely than adults to be volume depleted, and may respond favourably to a fluid bolus. The hyperventilation and respiratory distress seen in children with severe malaria is attributable to metabolic acidosis and severe anemia. Blood transfusion is therefore indicated in children with hemoglobin <50 g/L (<5 g/dl) who are from high-transmission zones. A more conservative threshold for transfusion of hemoglobin, <70 g/L (<7 g/dl), can be applied to those with severe anemia who reside in low-transmission zones or are residents of the developed world who have returned from travel to an endemic area.

Fluid therapy in the context of severe malaria remains controversial, and must be assessed on an individual basis. A balance must be struck between the risk of fluid overload, to which adults with severe disease are particularly vulnerable, and dehydration, which will necessarily worsen concomitant renal failure. Children with severe malaria are more likely than adults to be volume depleted, and may respond favourably to a fluid bolus. The hyperventilation and respiratory distress seen in children with severe malaria is attributable to metabolic acidosis and severe anemia. Blood transfusion is therefore indicated in children with hemoglobin <50 g/L (<5 g/dl) who are from high-transmission zones. A more conservative threshold for transfusion of hemoglobin, <70 g/L (<7 g/dl), can be applied to those with severe anemia who reside in low-transmission zones or are residents of the developed world who have returned from travel to an endemic area.

Acute pulmonary edema should be managed as per standard of care with supplemental oxygen, positive pressure ventilation if available and the patient is hypoxic, and therapeutic maneuvers that reduce preload on the heart, including diuresis, venodilation, hemofiltration, and dialysis. In patients with significant coagulopathy, vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma can be given. Correction of hypovolemia and anemia are key to ameliorating metabolic acidosis. To date, no other intervention has proven valuable.

Acute pulmonary edema should be managed as per standard of care with supplemental oxygen, positive pressure ventilation if available and the patient is hypoxic, and therapeutic maneuvers that reduce preload on the heart, including diuresis, venodilation, hemofiltration, and dialysis. In patients with significant coagulopathy, vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma can be given. Correction of hypovolemia and anemia are key to ameliorating metabolic acidosis. To date, no other intervention has proven valuable.

Seizures are a common complication of cerebral malaria, especially in children. Administration of intravenous benzodiazepines is the mainstay of treatment of seizures due to cerebral malaria. The WHO currently recommends against use of phenobarbital in children with malarial seizures, due to its association with increased mortality (WHO, 2006). Preemptive administration of antiseizure medication is not recommended.

Seizures are a common complication of cerebral malaria, especially in children. Administration of intravenous benzodiazepines is the mainstay of treatment of seizures due to cerebral malaria. The WHO currently recommends against use of phenobarbital in children with malarial seizures, due to its association with increased mortality (WHO, 2006). Preemptive administration of antiseizure medication is not recommended.

Hyperparasitemia is a major risk factor for death from severe malaria. Parasitemia should therefore be followed every 6–12 h over the first 24–48 h of therapy. In addition to parenteral antimalarials, exchange transfusion or aphoresis has been touted as an effective way to reduce parasite burden, though evidence to support this maneuver is scant and it thus remains controversial. Its use should probably be limited to situations in which prognosis is grave, parasitemia is >30%, or parasitemia is >10% with accompanying evidence of end-organ dysfunction including cerebral, pulmonary, or renal manifestations.

The continued high rate of mortality in severe and cerebral malaria has led to the investigation of a number of adjuvant therapies for P. falciparum malaria including corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies to TNFa, TNFa inhibitors, heparin, prostacyclin, and desferroxamine. None of these adjuvant therapies has proven efficacious in clinical trials, and therefore none is recommended.

In cases of severe malaria, where presentation is that of a systemic febrile illness with evidence of multisystem involvement, the concurrent use of parenteral broadspectrum antibiotics should be liberal. Intercurrent bacterial infection is common, particularly in children, and may be overshadowed by the diagnosis of malaria. Thus, this entity must be anticipated, especially in the setting of unexplained deterioration despite effective antimalarial and supportive therapy.

Because P. falciparum infection in pregnancy is associated with low birth weight, adverse fetal outcome, severe maternal anemia, and increased risk of severe sequelae, particularly pulmonary edema and hypoglycemia, administration of antimalarial therapy must not be delayed. Prompt initiation of parenteral therapy is indicated in pregnant women with severe malaria. In later stages of pregnancy, artesunate may be preferred over quinine due to the latter’s association with recurrent hypoglycemia.

Pharmacotherapy of uncomplicated malaria is summarized in Table 4. Unless a patient cannot tolerate oral medication due to vomiting or is believed to have poor gastrointestinal absorption, therapy of uncomplicated malaria should be via the oral route. Outside of Africa, P. vivax is the predominant species causing disease. P. vivax and P. ovale have a persistent liver phase that is responsible for clinical relapses. In order to reduce the risk of relapse following the treatment of symptomatic P. vivax or P. ovale infection, primaquine may be indicated to provide ‘radical cure.’ Primaquine use is contraindicated in pregnancy; therefore, P. vivax and P. ovale infections occurring during pregnancy should be treated with standard doses of chloroquine. Relapses can then be prevented by weekly chemosuppression with chloroquine until after delivery. Because of primaquine’s oxidant hemolytic potential, patients should undergo testing for glucose-6phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency prior to initiation of primaquine therapy.

Hyperparasitemia is a major risk factor for death from severe malaria. Parasitemia should therefore be followed every 6–12 h over the first 24–48 h of therapy. In addition to parenteral antimalarials, exchange transfusion or aphoresis has been touted as an effective way to reduce parasite burden, though evidence to support this maneuver is scant and it thus remains controversial. Its use should probably be limited to situations in which prognosis is grave, parasitemia is >30%, or parasitemia is >10% with accompanying evidence of end-organ dysfunction including cerebral, pulmonary, or renal manifestations.

The continued high rate of mortality in severe and cerebral malaria has led to the investigation of a number of adjuvant therapies for P. falciparum malaria including corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies to TNFa, TNFa inhibitors, heparin, prostacyclin, and desferroxamine. None of these adjuvant therapies has proven efficacious in clinical trials, and therefore none is recommended.

In cases of severe malaria, where presentation is that of a systemic febrile illness with evidence of multisystem involvement, the concurrent use of parenteral broadspectrum antibiotics should be liberal. Intercurrent bacterial infection is common, particularly in children, and may be overshadowed by the diagnosis of malaria. Thus, this entity must be anticipated, especially in the setting of unexplained deterioration despite effective antimalarial and supportive therapy.

Because P. falciparum infection in pregnancy is associated with low birth weight, adverse fetal outcome, severe maternal anemia, and increased risk of severe sequelae, particularly pulmonary edema and hypoglycemia, administration of antimalarial therapy must not be delayed. Prompt initiation of parenteral therapy is indicated in pregnant women with severe malaria. In later stages of pregnancy, artesunate may be preferred over quinine due to the latter’s association with recurrent hypoglycemia.

Pharmacotherapy of uncomplicated malaria is summarized in Table 4. Unless a patient cannot tolerate oral medication due to vomiting or is believed to have poor gastrointestinal absorption, therapy of uncomplicated malaria should be via the oral route. Outside of Africa, P. vivax is the predominant species causing disease. P. vivax and P. ovale have a persistent liver phase that is responsible for clinical relapses. In order to reduce the risk of relapse following the treatment of symptomatic P. vivax or P. ovale infection, primaquine may be indicated to provide ‘radical cure.’ Primaquine use is contraindicated in pregnancy; therefore, P. vivax and P. ovale infections occurring during pregnancy should be treated with standard doses of chloroquine. Relapses can then be prevented by weekly chemosuppression with chloroquine until after delivery. Because of primaquine’s oxidant hemolytic potential, patients should undergo testing for glucose-6phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency prior to initiation of primaquine therapy.